TWO AND A HALF MILLION YEARS AGO, in the Afar Desert of Ethiopia, history’s early butchers figured out a way to turn a dead animal into the evening meal.

Archaeologists near the Afar town of Bouri in 1999 uncovered prehistoric antelope bones scarred with scratches from rocks that they believe the ancients used as knives. Their discovery pushed back the time that our human ancestors butchered meat by more than a million years.

“We’re right at the beginning of the great leap that followed meat eating,” UC Berkeley’s J. Desmond Clark said at the time, and this consumption of meat allowed some early hominids – that is, upright walking apes – to outlast others, creating a line of evolution that eventually led to Homo sapiens.

A decade later, another team of archaeologists, from the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig, said hominids may even have used tools to butcher meat 3.4 million years ago.

As if channeling the spirits of their ultra-ancient ancestors, Ethiopians today cherish meat, so much so that some of them spend more than 200 days of the year not eating it. When the time arrives to break these vegetarian-only fasts, meat becomes even more prized and delectable.

“Meat plays pivotal and vital parts in special occasions and its cultural symbolic weight is markedly greater than that accorded to most other food,” Semeneh Seleshe writes in his 2013 study, Meat Consumption Culture in Ethiopia. “The consumption of meat and meat products has a very tidy association with religious beliefs and is influenced by religions. The main religions of Ethiopia have their own peculiar doctrines of setting the feeding habits and customs of their followers.”

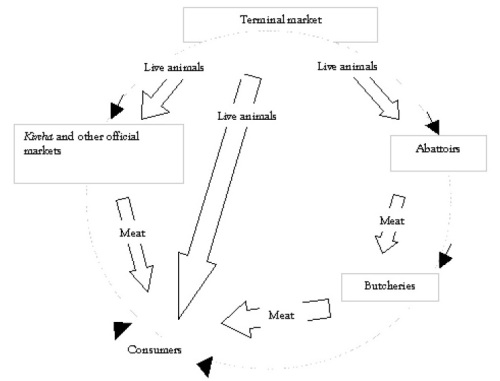

In fact, Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity has as many as 250 “fasting days,” which means no food before midday and no meat when you finally have a meal. Semeneh says that 62 percent of Ethiopian Christians observe in this way, and about 85 percent of butchers in Addis Ababa close on Wednesdays and Fridays, which are fasting days. Ethiopian Christians also eschew meat during the Lenten period and before Christmas.

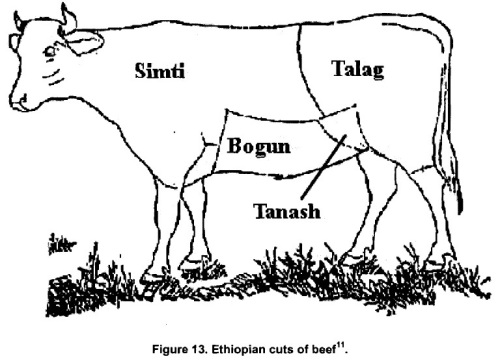

In their thorough (perhaps definitive) 1985 essay, Ethiopian Meat (Beef) Cut, Tsehay Neway and Feseha Gebreab studied beef cuts in the cities of Debre Zeit, Modjo, Nazareth, Dukam, and their surroundings in the center of the country, not too far from Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital. (Professor David Humber has created these excellent illustrations showing the cuts of beef, mutton and chicken.)

To identify their 14 cuts of beef, the researchers, both on the faculty of veterinary medicine at Addis Ababa University, slaughtered a year-old steer at the school and talked with local butchers and community elders.

They also drew on data from the slaughter of 40 other animals in a traditional manner known as kircha, wherein a large group of people – as many as 20 or 30 in a community – share the animal. Every part of the animal – meat, organs, bones – goes to people in the group in equal portions.

As Semeneh describes the practice: “A cow or an ox is commonly butchered for the sole purpose of selling within the community. On special occasions, people have a cultural ceremony of slaughtering the cow or ox and sharing among the group, which is a very common option for the people in rural areas where access to meat is frequently challenging.”

Tsehay and Feseha don’t delve very deeply into these cultural elements of sharing the meat, focusing instead on the practice of butchering the animal.

“Meat is one of the most universally liked foods,” their report begins, “and people in a11 parts of the world have established their own way of cutting and preparing meat for consumption. Therefore, there are now, in every civilized society, traditionally accepted modes of cutting meat. Different cuts of meat vary greatly in tenderness and it is possible that the cuts are prepared with the state and mode of consumption in mind.”

The scholars found that “no two meat cuts of similar origin are identical. The uniformity of the cut largely depends upon the experience and ski11 of the butcher and the sharpness of the knives at his disposal.” And they say that in urban areas, “marketing trends” have led to “some meat portions of inferior quality with traditionally recognized first class cuts.” Even in Ethiopia, it seems there’s nothing like good home butcherin’.

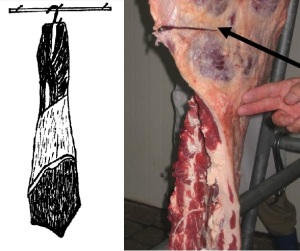

Needless to say, it takes some skill and training to partition a large animal into so many clearly defined cuts of meat. USAID, an agency that aids development around the world, has published a vividly illustrated and detailed guidethat teaches Ethiopians how to butcher an animal, although the guide notes that it’s “not a substitute for hands on practical training.” Where Tsehay and Feseha use drawings in their essay to show the cuts of meat, the USAID guidebook uses many color photographs. Another USAID booklet shows a variety of Ethiopian meat cuts prepared for export.

Here, then, are the 14 cuts that Tsehay and Feseha identified, all named in Amharic, the state language of Ethiopia. They may well have different names in other Ethiopian languages, like Tigrinya and Oromo. The researchers’ descriptions often use medical terms to refer to body parts, so I’ll try to simplify. And I’ll use the generic term “cow” to refer to the animal, although understand that the cattle raised in Ethiopia is different from the cattle we raise in the west (see photos below).

I should note that these are traditional cuts, and in modern Ethiopian butcher shops, partitioning the animal is often simplified into cuts good for three kinds of dishes: qurt (raw chunks of meat), tibs (fried in spiced butter, often with sliced onions or peppers), and wot (cooked in a thick onion sauce).

♦ Shent. Ethiopians love to eat raw meat, and there’s no finer cut for it than shent. The word refers to the side of the body, so this cut comes from the neck and rump, “long and slender and largely made of soft and juicy flesh. Shent is number one in choice for raw consumption. It is also enjoyed as pan broil or braise. It is in fact a well-esteemed gift that can be presented to close friends and relatives.” In American parlance, this would be a rib-eye steak.

♦ Bete Salgegne. Another fine cut of meat, the name refers to “the difficulty in obtaining this cut in predetermined uniform pieces since it is always subject to variations due to its position in the carcass.” A combination of meat from the shoulder, ribs and brisket, it brings a higher price if it contains more fat, called marbling in the meat business. In the zebu, a humped Ethiopian species of cattle, this cut is nicely marbled and goes by the name shanga (“sha-nya”). It, too, is good for raw dishes and to give as a gift.

♦ Tanash. This cut comes from a variety of places: some soft juicy marbled muscles, and some tougher tendons, so it’s not ideal for a raw meal.

♦ Fremba. This cut comes from “the breast, short plate and the flank, with the exclusion of the sternum and ribs,” and it’s made up of “fleshy muscles well impregnated with fat.” It, too, can be eaten raw, although it’s not as fine as the other preferred raw cuts.

♦ Talak. This is “the meat of choice for preparation of the national dish known as kitfo,” which is raw chopped beef seasoned with niter kibe and mitmita (spiced butter and hot red pepper). The authors also say that despite the presence of pubic bones, it’s considered to be a boneless cut, and the small amount of bone allows butchers to hang the meat on a hook.

♦ Mehal Ageda. Here’s a very precise cut made up of one muscle and the bone associated with it so it can hang from a hook. The name means “central cane” because of its central location on the animal, and it’s good for making kitfo.

♦ Nebro. This is fleshy belly meat “infiltrated with tendon.” The name is Amharic for tiger because of “the strength of the muscle whose fibrillation is also considered to be similar to the expressions of the furious animal during moments of wrath.”

♦ Tuncha. Good for braising, the fleshy tuncha comes from the muscles of the leg and foot of the animal.

♦ Nekela or Nikay. Need to feed a family? Then consider this cut, composed of talak, mehal ageda, nebro and tuncha, with bones of the thigh and leg. This makes it especially convenient for consumers because they can use the various portions however they choose.

♦ Goden te Dabit. This cut comes from the animal’s first seven ribs and the muscle and connective tissue that goes with it. Two of the muscles are fleshy and marbled, and one of those two, the dabit, makes a good raw meal. The rest of this cut is better cooked.

♦ Gebeta. Here’s a diverse and complex piece of meat, “made of the inner part of the breast, short plate, flank and brisket. It is composed of half of the sternum, asternal ribs with their cartilages.” Part fleshy, part tendonous, the name means “naked” and refers to the fact that it removes the fremba – that is, the fleshier marbled meat that comes from these areas of the animal.

♦ Sebrada. This term refers to the last two ribs on a cow, and also “the last two floating ribs in man.” The meat of this cut comes from the muscular and fleshy parts of the ribs.

♦ Chekena. A sub-cut of sebrada, the chekena (or cheqena) comes from the soft tender flesh of the iliopsoas muscle, sold separately and “consumed roasted or pan broiled,” while the rest of the sebrada cut is braised. The word chequn means “poor person,” so this is sometimes considered to be a poor man’s cut of meat. From time to time, on menus at Ethiopian restaurant, you’ll find chekena tibs. Most restaurants spell it chikina tibs, though, which at first glance might make you think it’s a chicken dish. But chekena is a better transliteration of the Amharic, and cheqena is better yet.

♦ Werch. A low grade of meat, best eaten cooked, werch comes from the animal’s muscular shoulders and arms. Some of it is fleshy, but much is heavy with tendon.

♦ Dendes. This cut, last and least, “is not fit to be included amongst the ranks of proper meat.” It’s made up of a mass of bone and pieces of flesh detached from parts of the animal’s last lumbar vertebra. Fortunately, you’ll never find dendes tibs on an Ethiopian restaurant menu.

THE EMINENT ETHIOPIAN SCHOLAR Richard Pankhurst writes about some of these cuts of beef in his 1986 essay, The Hierarchy of the Feast: The Partition of the Ox in Traditional Ethiopia. Cattle was very important in ancient Ethiopia, but even if you owned a cow that you planned to use for food, a commoner couldn’t slaughter his cow without permission from the local ruler. No doubt the ruler got a portion of the slaughtered animal in thanks for his permission, Pankhurst speculates.

Pankhurst’s fascinating essay details every aspect of a royal banquet, which was highly ritualized. Each part of the slaughtered cow produced a cut of meat with a name of its own: tanash sega, or “small meat,” came from “the rump bone down to the hind quarters,” the goden dabit were “five of the foremost ribs,” the engeda is “a prime fleshy part, taken from the muscle close to the thigh bone,” and shent comes from “the side of the backbone as far as the shoulder.” Of course, the revelers ate all of this meat raw.

Two regional Ethiopian cattle breeds: Arado (l), from northern Tigray;

and Afar, from the northeast Afar region

In the mid-19th Century, Emperor Yohannes IV ended the practice of seeking permission to slaughter an ox, although in some Ethiopian cultures, the custom persisted: Local rulers might be entitled to the animal’s lesana manka (the tongue and breast meat) if a member of his town slaughtered an animal for a special occasion, like a marriage, funeral or holiday celebration.

Pankhurst’s essay – his information drawn from historic accounts – explores how law and custom prescribed who got what upon the slaughtering of an ox. People of the highest ranks got such prized cuts as the “small meat” from “the rump bone down to the hind quarters,” or the “large meat” from the hip bone with part of the buttock. These succulent steaks were just some of the portions that went to the aristocrats, and it’s hard to believe there was very much of the good stuff left after the upper classes got their tributes.

But there’s a downside to this love of beef, especially in modern times, when a cow isn’t what it used to be.

In 1979, the Los Angeles Times reported the results of a study of 130 Ethiopian college students, construction workers and bank employees.

Heart attacks were rare then in Ethiopia because of the country’s traditional low-fat, high starch diet. Construction workers, who ate mostly “whole grain bread, vegetables, peas and tea,” had an average cholesterol level of 110. College students, adding fat from things like margarine and sausage to the traditional foods, came in at 160. The bankers ate more meat, butter and eggs, and their cholesterol was 180.

Back then, a 2012 report from Addis Ababa declared, “cardiovascular diseases were mainly considered the problem of the developed world just a few decades back. However, currently, reports suggest that it is becoming a primary health concern for middle- and low-income countries.”

Doctors in Ethiopia say that “for long-time raw meat lovers, the taste has changed a lot. The change, they say, is the way the oxen are fattened. In the old days, the meat always came from naturally grown cattle. The elders say that cattle in the old days ate naturally grown grass, which has a lot of organic and healing contents.” But meat today is more marbled – that is, it contains more tasty fat – and that has increased cholesterol levels in people who eat a lot of it.

SO WHAT, IN THE END, do you do with all of this meat? How do you prepare it and serve it?

If you want to eat it raw the way they enjoy it in Ethiopia, you have several options: gored gored is chunks of tere siga (literally, “raw meat”) that you can dip in awaze, a hot pepper sauce; kitfo, a favorite dish that comes from Ethiopia’s Gurage culture, is ground raw meat seasoned with mitmita and cardamom, then cooked in niter kibe; and qurt is a long strip of raw meat that you cut into pieces yourself with a knife (the ritual of doing it is part of the fun of the meal).

In addition to tere siga, another general word for raw meat is brindo. And this way of eating meat is strictly for adults: You have to reach a certain age before your parents will let you have raw meat. Like all things with parenting, the age depends on the family.

Three beef dishes: gored gored, chunks of raw meat; derek (“dry”) tibs,

fried in Ethiopian butter; and siga wot, a spicy stew

Boston University’s James McCann, one of the world’s foremost scholars on Ethiopian food, says that reaching the age at which you can eat raw meat “is a marker of post-adolescence, like long pants.” And he notes that people in Ethiopia see raw meat differently than expats in America.

“Raw meat is very rare in the diet, so children would not be high on the pecking order,” he says. “Expatriate Ethiopians have lots of cultural myths that claim historical background, but really only date from the Addis Ababa elite or upper-middle-class practice in the mid-20th century. Raw beef cut in chunks or strips has been around for a long time. Kitfo is a fairly recent addition to urban diet, but it is popular. And there is an exception to every rule given regional variation.”

He notes, for example, that you’ll find no mention of kitfo in Impressions d’Éthiopie (1913), written by the Frenchman Paul Merab, who was Emperor Menelik’s French-speaking doctor (née Petre Mérabichvili in the republic of Georgia). His memoir provides a detailed account of “21 distinct culinary preparations that he reckoned made up the national cuisine of the day.” Mereb called his list “le cordon bleu etiopienne.” Nor does Harold Marcus, a renowned Ethiopian scholar and one of McCann’s teachers at Michigan State University, mention kitfo in his accounts of Emperor Menelik’s early 20th Century feasts.

A 2012 study of meat consumption in Ethiopia confirms McCann’s assertion about the rarity of meat in the Ethiopian diet, despite the culture’s love of it.

“Ethiopia is known to have one of the largest livestock populations in the world,” the report says. “Yet the overall contribution to Ethiopian households’ daily consumption is very limited. At the national level, the average per capita annual consumption of meat and dairy products is just 5.3 kg and 16.7 kg, respectively. The consumption of livestock products, however, varies considerably between urban and rural areas. Urban areas have higher consumption of meat, whereas rural areas have higher consumption of dairy products.”

Two more things to note about kitfo. First, in the Gurage culture from which it came into the national cuisine, you don’t eat it with injera the way you do other dishes. The Gurages scoop it up with long-handled spoons, often made out of animal horns. And your “bread” at the meal is traditionally qocho, made from the fermented trunk of the enset plant, sometimes called the false banana because it resembles a banana tree. The kitfo comes to the table displayed on a dark green enset leaf with some qocho on the side. You might also get a side of ayib, the fluffy white Ethiopian cheese, and the ayib may have some gomen (collard greens or kale) mixed into it, making it a dish called zemamoojat.

For those who prefer their meat cooked, siga wot is the basic dish: chunks of meat stewed in kulet, a thick sauce of onions, berbere (another red pepper powder) and niter kibe, plus a few other spices (chef’s choice). This is my personal favorite. The mild variation is siga alicha, where the spices are ginger and turmeric rather than red pepper. Derek tibs are pieces of beef fried up in niter kibe, with onions and jalapeño peppers tossed in. The word derek means “dry,” so you won’t get any juicy kulet with this variation. Minchet abish is cooked ground beef seasoned with fenugreek (abish in Amharic).

Another view of dividing up the cow, from a dissertation by Nicholas Weber

Or you might try goden tibs (Ethiopian short ribs of beef, lamb or goat) or, if you can find it, some qualima or wakalim (varieties of Ethiopian sausage). Rarer still is ouatala, salted and spiced cuts of fat from the hump of the zebu (an African cow) that begin to taste like smoked ham after they’re hung for a while from the back of the house. And let’s not forget quanta, the Ethiopian beef jerky – dried, chewy and spicy hot. You can even cook quanta in a kulet to make a saucy beef entrée.

Restaurant menus can sometimes get a little confusing because of the sub-categories or alternative names of these basic dishes. Zilzil tibs, for example, is essentially derek tibs with the meat cut into strips rather than chunks. Kay wot (or quy wot) is just a more descriptive name for siga wot – kay means “red,” which tells you that there’s hot pepper in it. Dishes like shent tibs or chekena tibs refer to the cut of meat that the restaurant uses. I’ve seen the dish kintot (or qintot) on menus, taken from the Amharic word for “luxury,” so this means a dish with lots and lots of meat.

But you really needn’t worry about what your dish is called: Just read the menu description, ask a few questions, order some veggie side dishes – gomen and ayib go especially well – and relish your meat like an Ethiopian.

University of Pittsburgh

Butchering and eating raw meat in Ethiopia:

Visit an Ethiopian butcher shop in Toronto:

Ashu Grocery is a well-known butcher shop in Addis Ababa:

Leave a comment