(This is the second of a two-part look at how newspapers reported information about Ethiopian cuisine. Part one examined the century before America had any Ethiopian restaurants. I’ve standardized the spellings of all Ethiopian foods in the excerpts from the newspapers. The links take you to many of the original stories.)

FOR DECADES, OCCASIONAL MORSELS IN NEWSPAPER STORIES had to suffice to fill our minds rather than our bellies with Ethiopian food until cities had the chance to taste it for themselves. Finally, though, our country’s first Ethiopian restaurant opened in 1966 in Long Beach, Calif. The community learned about it from a squib that appeared on page A-24 of the Long Beach Press-Telegram on July 21, 1966:

FROM THE LAND OF THE QUEEN OF SHEBA – Definitely the most unusual new café in town is the Ethiopian Restaurant, 732 E. 10th St. It’s a former house converted into a modest dining place which seats 30 in two rooms. The owner is Beyene Guililat, a young Ethiopian man who is in this country studying to become a commercial air pilot. His dinners consist of authentic native dishes, including chicken. They’re from $2 to $4, according to how many courses you wish.

Beyene was more of a dreamer than a businessman, so his restaurant only lasted for a few months. But he started something that many other immigrant Ethiopians would make flourish.

Three years later, Beyene revived his Ethiopian Restaurant at 248 W. Washington St. in San Diego, and the San Diego Union wrote about his unique enterprise.

On Jan. 9, 1969, columnist Frank Rhoades published a squib about the restaurant’s impending launch. “The place is being remodeled and Beyen [sic] Gulilat, formerly of Long Beach, has applied for a health card, but job hunters, vendors, etc., can’t find him,” Rhoades wrote. “And none of them know what is Ethiopian food.”

Beyene eventually turned up, and his restaurant opened. In the newspaper’s March 9, 1969, issue, he told Rhoades that he prepared enough food every day for 40 meals, and he sometimes had to turn people away.

“I am not in business to make money,” Beyene said, “only to introduce the culture of my country. I am very proud of it, and the patrons all seem delighted with my chicken and beef.” Rhoades adds that Beyene was enrolled at the local Mesa College and was studying to be a pilot for Ethiopian Airlines.

Perhaps inspired by Beyene’s Long Beach debut, the Los Angeles Times ran a piece on Oct. 20, 1966, with chicken recipes from around the world, including one for “Ethiopian Chicken” that replaced berbere – unknown to Americans, and impossible to get at the time anyway – with chili powder (cayenne would have been a better choice). The recipe sounds vaguely like doro wot, copiously adapted for the impatient and inexperienced American home chef.

A June 16, 1966, article in the LA Times makes an amusing mistake. Writing about breakfast foods from around the world, the writer says that “Ethiopians cook kimchi from wheat and eat it with chike, a kind of barley bread.” He got the second dish right, but the first one is a porridge called kinche (or quince). The dish he names is spicy fermented Korean cabbage.

Meanwhile, on the east coast, The New York Times had begun to discover the cuisine.

A 1957 story, “Ethiopia Soon To Be in Full Bloom,” discussed the country’s “peppery cuisine” featuring t’ej, injera and wot, “a highly spiced sauce in which about 30 different kinds of herbs and seasonings have been cooked for hours.” The writer describes the method of eating, then adds, “Addis Ababa hotels will provide a native menu once a week on request, but they will include plates, knives and forks.”

A 1958 Times piece on tourism in Ethiopia takes readers to dinner at the prime minister’s residence under an enormous tent with “a buffet about a half mile long.” The drinks include vermouth, gin and “the local aquavit” – probably areqe, the Ethiopian ouzo – and the buffet featured raw meat. The writer, Hedy Maria Clark, says she “disappointed my hosts by failing to shudder at the raw meat.”

On Nov. 19, 1966, Thomas F. Brady’s New York Times story about a conference of African leaders in Addis Ababa describes a state dinner: “Everyone carefully tasted the Ethiopian delicacies – a soft, flat, spongy gray bread that looked like tripe and had a pleasantly sour taste, and a meat stew so highly laced with pepper that the guests had to wash it down with a lot of t’ej, an Ethiopian mead or a fermented drink made of honey and water. The classic component of an Ethiopian banquet, raw meat, was left off the menu, apparently out of consideration for foreign palates.” He doesn’t tell his readers the name of this bread.

Then, in 1970, The Times published a story about the Kalamazoo Spice Co. in Michigan and its innovative collaboration with farmers in Ethiopia. The company sought new sources of chili peppers and found that the climate of Ethiopia was perfect for growing them. So with the help of USAID, the Kalamazoo company built an $800,000 plant on the outskirts of Addis Ababa and hired 25 farmers to raise peppers on 100 acres of land.

But it might not have been entirely a coincidence that the company chose Ethiopia. Dr. Selashe Kebede was a graduate of Michigan State University, where the Ethiopian native had been part of a research project sponsored by the spice company. So when the company launched its Ethiopia venture, it hired him as an executive to oversee it.

Eight years later, Selashe and his wife, Workinesh Nega, made Ethiopian-American food history: In Kalamazoo, they created Workinesh Spice Blends, the first company to sell Ethiopian spices and American-grown teff in the United States. Rather than importing her spices from Ethiopia, Workinesh made them herself, growing her company and soliciting business by reaching out to the Ethiopian-American community. She and Selashe retired in 2007 and moved back to Ethiopia, and their daughter, Lemlem Kebede, who has a degree in advertising, now runs Workinesh Spice Blends from St. Paul, Minn. The company has no website – and apparently doesn’t need one.

In 1970, American cookbook author Beatrice Sandler, left, prepared an Ethiopian meal in New York City, nine years before the city had an Ethiopian restaurant.

To mark the emperor’s 40th anniversary on the thrown, The Milwaukee Journal published a short wire service story in 1970 by a writer who tried to be playful when he talked about food.

At a meal, the writer said, “you sit around tables of ornate basketwork over which your waiter drapes an enormous gray tablecloth (that looks, in fact, rather like foam rubber). Another servant ladles ‘wot’ straight onto the cloth. No fuss and nonsense about plates, knives and forks. All you do is tear off a piece of the tablecloth, which is, in fact, a kind of bread, wrap it around you know what – wot – and guzzle away.”

And then there’s his description of the wine: “You wash [the food] down with a wine that exists nowhere else in the world. It’s called t’ej, and consists of nothing more or less than fermented honey. You drink this straight from the carafe. No glasses. Selling dishwashing machines to the Ethiopians must be tougher than selling refrigerators to the Eskimos.”

His “carafe” is a berele, a long-necked, round-bottomed vessel for drinking t’ej (see image below). And his wine made “nowhere else in the world” is simply the Ethiopian version of mead.

Little Ardmore, Okla., population 25,000 even today, got a very bad lesson in Ethiopian food in 1967 when The Daily Ardmoreite said farewell to a native daughter about to leave for Ethiopia with the Peace Corps. A professor at Oklahoma State University who had been to Ethiopia invited her to his home, where he and his wife served her an Ethiopian meal – more or less.

“She described the bread-like crust called wot,” the newspaper wrote, “which is the staple of the Ethiopian diet. Meat, which is very, very spiced, is wrapped up in the wot and eaten with the fingers.”

We’ll never know whether the professor, the young woman or the newspaper got it wrong, referring to injera as wot. “I took a big bite and tears came to my eyes,” she said of the meal. “I thought I was on fire. But five minutes after I quit eating it my mouth no longer burned.”

The town of of Reading, Pa., got a taste of Ethiopian food in 1967 when the Reading Eagle interviewed two local people who had just returned home from mission work in Ethiopia. “The basic menu is injera (a large pancake of sour bread) and wot (a highly seasoned stew hotter than Mexican food),” the story explains.

Mrs. Frank Weaver (we never learn her first name) then tells us that her children savored the spicy cuisine more than she did. “The infant mortality rate is high,” she says. “They have no baby food as we know it, and many of their young children can’t take the steady diet of injera and wot.” Her family also missed milk, which they didn’t drink in Ethiopia because it wasn’t tested for tuberculosis. The country has lots of fresh fruit, she said, but she had to soak it in chlorine before eating any to ward off dysentery.

And despite what we know about famine in Ethiopia, Mrs. Weaver observes: “They say Ethiopia could feed all of Africa if it could develop all of its resources.”

A 22-year-old college student from Reading returned home from Ethiopia in 1972 with some other culinary tales. Carl Filer told the Eagle: “They eat raw meat over there, and if you ask to have your food cooked, they’re offended.” He does say that Ethiopians “kill you with kindness,” to which the reporter adds parenthetically: “As if the raw meat wouldn’t be a sufficient method for most visitors.”

Twenty-five years later, the Reading Eagle again introduced locals to a unique aspect of Ethiopian food when it published a Los Angeles Times story about the enset plant which, in Ethiopia, is “dug up, scraped, moistened, and buried in a pit to ferment anywhere from a couple of weeks to a couple of months. Then it’s disinterred and made into porridge or bread.”

Although the story doesn’t say so, the porridge is called bula and the bread is qocho. The piece does say that the bread goes well with butter, cheese, “stewed meat” (i.e., wot) or stewed cabbage.

An interesting 1970 Associated Press story that appeared in many newspapers notes a particular aspect of Ethiopian dining that rarely gets mentioned: “One takes a bit of the injera (the pancake) in his right hand (the left is for ‘other things’ and not eating) and captures a bit of wot with it before popping both into the mouth.” This is true: Ethiopians only eat with their right hands, and tearing off a piece of injera with just one hand is a challenge at first.

Craig Claiborne published several lengthy pieces in The New York Times in 1970 that described his encounters with Ethiopian food during his time in Addis Ababa. The stories also appeared in many other newspapers around the country, providing readers with a solid account of Ethiopian cuisine.

In one piece, Claiborne talks about injera, wot, t’ej and more, and he offers cooking lessons through the courtesy of Mrs. Assegedsh Walde, the “utterly charming” owner of Mara Denbeya restaurant, which offered both sit-down dining and takeout meals.

“There are, in general, two reactions to the native food of Ethiopia,” Claiborne wrote. “It is consumed with considerable ardor or eschewed with comparable passion. In the American-European world, it resembles as much as anything the food of Mexico but only in its thoroughgoing use of hot red and green peppers. Most of the main dishes of the Ethiopian kitchen are based on berbere, which is nothing more than dried hot red chilies. The food is, to my mind and taste, among the world’s most interesting, and it is taken in the most convivial manner.”

At a meal in the Harrar Grill of the Addis Ababa Hilton, he feasted on yebeg alicha, a “tender lamb dish flavored with bishops weed and saffron”; doro wot, “the Ethiopian chicken and hard cooked egg dish with a light pepper sauce”; and minchet abish, “a ground beef dish that tasted lightly of cinnamon and pepper.” He also had gomen wot, made with spinach and shallots (“delectable”), and t’ej (“fascinating”).

Emperor Menelik II’s berele,

used for drinking t’ej

He notes that the hotel’s restaurant also serves Western cuisine, like bacon and eggs, sirloin steak, rack of lamb, roast chicken and baked lobster. In fact, if you want the Ethiopian feast, you have to order it five or six hours in advance for at least two and preferably even more people. Or you can have a “less elaborate but nonetheless excellent” Ethiopian meal any time in the hotel’s Kaffe House coffee shop.

Claiborne eventually made his way to Eritrea, which was then Ethiopia’s northern province, and he noted the strong influence of Italian cuisine in the country, an Italian colony for half a century until the 1940s.

Still, he notes: “Here, as elsewhere in Ethiopia, the national dishes are injera, an excellent moist bread, and various kinds of wot, or stews, made from chicken, beef, lamb and so on.” His story focuses on the Italian cuisine of Asmara, but when he orders spaghetti, he chooses “a hot tomato sauce, the sauce most commonly used, they tell me, in Ethiopian homes.” This is true – in fact, Ethiopians use berbere to heat it up.

In another piece, Claiborne chatted at length with Beatrice Sandler, author of the newly published African Cookbook, about her travels around the continent with her niece – a “pretty young lady,” Claiborne writes – in search of authentic recipes.

They seemed to especially enjoy Ethiopia, where they “sat around a mesob, the traditional woven table that is roughly in the shape of an hour glass. The food, served in a ceremonious manner with honey wine, is placed on a round tray. The base of the food consists of circles of flat bread called injera.” Claiborne then describes the method of eating these “savory dishes – a lamb stew, perhaps, a cheese and yogurt relish, or a vegetable dish.”

Sandler says that her cookbook cools down the spice levels of the dishes because “otherwise, the food would be far too hot for the American palate.” The story concludes with five recipes, four of them Ethiopian, although one is the Queen of Sheba salad created by Kurt Linsi, the Swedish-born chef to Haile Selassie and Ethiopian Airlines in the ’50s and ’60s. (See part one of this story.)

Sandler lived in Miami Beach, Fla., and in 1973, she prepared a fund-raising African buffet for 400 people in her community that introduced them to the continent’s cuisine.

The Palm Beach Daily News wrote a front-page story about the event, and here’s what Sandler said about Linsi’s Queen of Sheba salad, which she included in her buffet: “In Ethiopia, nobody eats vegetables. The chef invented this salad dressing in order to get the emperor’s court to eat vegetables. Believe it or not, he put a little bit of pastrami in it.”

An assertion like this certainly makes one question the veracity of anything Sandler has to say about Ethiopian cuisine. Ethiopian Christians spend many religious fasting days each year not eating meat, often supplementing the meal with additional vegetable dishes. Perhaps she didn’t consider an Ethiopian wot or alicha to be a vegetable, or maybe she was so shocked by the Ethiopian love of raw meat that it blinded her to everything else they ate.

Fortunately, Claiborne’s more thorough reporting offered a good introduction to the cuisine for New Yorkers, who wouldn’t get their own Ethiopian restaurant until 1979, although berbere is certainly more than just chili peppers, and injera, as he later says, is not made with millet.

The New York Times syndicates its stories, so people across the country read Claiborne’s work as well. In fact, in 1979, a Q&A column of his appeared in the Register-Guard of Eugene, Ore., with the question: “At a recent buffet, a principal item was a casserole called a wot. The food in the casserole was served on top of hard-cooked eggs. Someone said it was either African or from Hong Kong. Have you ever heard of a wot?”

Well, yes, he had, in Ethiopia, “where wots of one form or another are probably the national dish. Basically, the word wot means a stew. It may be made with meat, poultry, fish or vegetables. These stews are generally elaborately spicy, not only from hot ground peppers, but from other spices such as cardamom, allspice, fenugreek and so on.” Four years later, just 110 miles north, Portland, Ore., got its first Ethiopian restaurant.

If Southern California had more Ethiopian restaurants after the demise of Beyene’s pioneering 1966 restaurant – along with his 1969 restaurant in San Diego, which also didn’t last long – they kept a low profile. The Los Angeles Times didn’t mention one until more than a decade later, and even after that, the newspaper’s writing about the cuisine is scant through the ’70s.

“You have heard of an Ethiopian restaurant,” food columnist Lois Dwan wrote in 1979. “Very good reports, too. It is Walia, 5881 W. Pico Blvd.” The city had at least four restaurants by 1981, and in the 1990s, not far from West Pico, a two-block stretch of South Fairfax Avenue had become a gathering place for Ethiopian restaurants and markets, so the city dubbed it Little Ethiopia. By then the cuisine had begun to spread to big American cities.

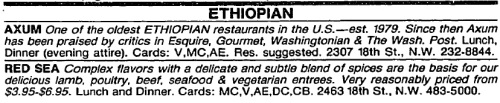

The LA Times listed Walia in an April 1980 dining guide for people who didn’t want to eat at home for Easter. The restaurant’s holiday package offered “traditional Ethiopian dishes plus champagne,” along with “a meat turnover in flaky pastry, salad, roast baby lamb, and vegetables, plus Ethiopian custard baklava.” The turnover is a sambusa, and that last one, a Walia original, is what we might call a cross-cultural diaspora accommodation. And a July 1981 LA Times piece, “A Taste for the Exotic,” included thorough squibs on four Ethiopian restaurants: Walia, Almaz, Red Sea and Addis Ababa.

The globetrotting New York Post journalist Leonard Lyons visited Ethiopia in 1971 and filed a series of reports for his syndicated Lyons Den column. He described the hand-washing ritual at an Addis Ababa restaurant, where “the waiter, at the beginning and end of the meal, brings a brass basin with a cake of soap. A towel is hung from the waiter’s forearm, and he proceeds to pour some water over each guest’s hands from a brass-covered pot with a large spout.”

Lyons also tells a quick anecdote about Poppy Cannon, an American who visited Addis and went to markets to get supplies “to try to make minchet abish, cheguara alicha, beer and hydromel t’ej. This last one is made by using 1,500 kg. gesho, 4 kg. honey – raw (comb) – and 16 liters of water.” The recipe comes from Ethiopian American Cook Book, which has Ethiopian and western recipes written in both English and Amharic. Cheguara is beef tripe, and gesho is a plant whose wood and leaves Ethiopians use to flavor their t’ej.

Residents of Newburgh, N.Y., got a quick taste of Ethiopian food in 1971 in a story about two exchange students living nearby. The young women said they missed injera and wot, “which they explained was a pancake-like bread made only from African grain, and a pepper, onion, butter and meat spread.” The story adds that “Ethiopian coffee is traditionally made in the Turkish way, thick and black.”

That same year, soon-to-be-disgraced Vice President Spiro Agnew visited Ethiopia and attended a state luncheon with “Western-style food, Ethiopian dishes, wine and t’ej, the Ethiopian national drink, made from honey, water and hops.” One only hopes that the emperor counted the silverware before Agnew left the country.

Across several ponds, the residents of Melbourne, Australia, got an introduction to Ethiopian food in a 1971 story in The Age about – well, I’m not sure. It’s a theater column by Pat Dreverman that consists mostly of an interview with a fellow named Derek Nimmo, who talks about after-theater dining in Melbourne and shares some international culinary adventures.

He had visited Ethiopia a while back, and this is what he had to say about the food: “Lunch consisted of something that looked like cold soggy Dunlopillo, some very potent wine, and water to wash it down. Now I know why you never see Ethiopian restaurants in any other part of the world.” The wine was certainly t’ej. As for Dunlopillo: It’s a brand of British-made latex foam used in bedding – not exactly an appetizing experience for Australian readers.

The next year, The Age had a much more upbeat account of Ethiopian cuisine thanks to Nancy Dexter, who visited the country and wrote about it for the newspaper. Only a few hundred Ethiopians lived in all of Australia at the time.

“The food?” Dexter begins in her passage about cuisine. “Let’s face it, Ethiopia isn’t Rome or Athens, with little restaurants dotted here and there.” She had a meal at “the only home-grown place I found, a restaurant built in the shape of a tukul, the round thatched huts seen in many parts of the country.”

She is quick to note, however, that “real tukuls don’t have velvet-covered divans and three-legged stools covered with long black and white monkey fur. And they don’t have hand-made, basket-woven tables.” This is the traditional mesob, a term she never uses.

Her servers bring her pieces of injera 18 inches in diameter – injera is much bigger in Ethiopia than in American restaurants – and she found it to be “filling and tasty,” even if it does “look and feel a little like fine tripe.”

Soon, she was presented with “spoonfuls of curries,” which she ate in the traditional way, grabbing it with injera. “Europeans are easily distinguished by the mess they get into,” she adds. She and her companions then enjoyed “little individual carafes of honey wine” – this would be t’ej served in a berele, two more terms she doesn’t share – and cardamom-flavored coffee.

She enjoyed one other meal of Ethiopian food while in Ethiopia, at a birthday party for the mayor of Addis Ababa. The injera, she reports, “was reduced from platter size to hors d’oeuvres dimensions, some of it flavored with spices and tasting like spongy gingernuts.”

Dexter then notes the presence of a beloved element of Ethiopian cuisine.

“Traditional Ethiopian food includes raw meat,” she writes, “served most untraditionally in small pieces on toothpicks. Raw meat is still popular with most Ethiopians, but evidently city hall tastes are more sophisticated. It was conspicuous by its unpopularity.” The meal ended with an eight-tiered iced birthday cake topped with a crown.

Seattle has a huge Ethiopian community today. But not in 1972, when newspaper readers in Ellensburg, a hundred miles southeast of Seattle, learned of a neighbor who had lived and taught in Ethiopia and who hosted an Ethiopian dinner for friends. The meal began with Italian antipasto “followed by beef wot and vegetable wot (alicha). The Ethiopians tear pieces of bread (in this case the guests used soft taco shells) to dip or spoon the wot as no silverware is used.” Fruit for dessert took the edge off the meal’s fiery spices, which friends in Ethiopia supplied to their former colleague to allow him to make authentic Ethiopian food at home in America.

The Hillsdale, Mich., chapter of the American Association of University Women flunked their Ethiopian food test at a dinner they served in 1972. Titled “A Taste of Ghana,” the menu included mostly Ethiopian dishes. As described by the Hillsdale Daily News, the women served “keysur chingort (beet and onion salad), sray chingort (date and onion salad), komatata ater (green beans in sour sauce), injera (flat round bread), yemarina lewotet daboo (honey bread), yewollo ambasha (spice bread).” Most of those spellings are close enough – chingort (onion) should be shinkurt – but those dishes are all Ethiopian (more or less). The menu also includes such west African dishes as ochloni marac (peanut soup), gomo pidise (cabbage and bacon salad) and the ever-popular jollof rice. To be fair, the newspaper did say the meal consisted of “African dishes.” But considering the name of the event, most readers at the time surely would have thought they were learning about Ghanaian rather than Ethiopian cuisine.

For years later, is Muscatine, Iowa, another AAUW chapter got it right, serving an Ethiopian meal that included a hand-washing ceremony and a “tablecloth” of bread (injera) covered with siga wot, doro wot, atkilt qeqel (veggie stew), ayib (cheese) and t’ej. They women had dabo kolo for a snack before the meal and the very un-Ethiopian Monrovian pie with coconut for dessert – accompanied, thankfully, by Ethiopian coffee spiced with cinnamon, cloves and dark honey.

Before he became a TV icon hawking his eponymous popcorn, Orville Redenbacher traveled the world, teaching other cultures how to grow things, and he stopped in Ethiopia along the way. In 1973, a United Press International story appeared in papers across the country describing, among other things, his culinary adventures.

Redenbacher described a meal on a straw platter about 30 inches in diameter and covered with “a big pancake of teft with hot sauce in the center, and, ringed around it, barbecued beef, mutton, chicken and vegetables. He said teft is the main cereal grain of Ethiopia. It is a small grain that looks like grass. Everyone ate from the same platter using the fingers of one hand to tear off pieces of the pancake and dip them into the sauce, vegetables and meat.” Save for the misnamed “teft,” that’s all close enough, and it does note that Ethiopians only use one hand (the right one) to eat.

In June 1974, Professor John Rider of Southern Illinois University at Edwardsville told the local Intelligencer about his trip to Ethiopia. He didn’t describe a meal, but in a photograph with the story, he shows off a mudai, which is a smaller version of the mesob, the basket used to host a traditional meal. “The cone-shaped basketry object,” the story says, without naming it, “is a small model of the Ethiopian dinner table. The cone tip is removed, and meals are served on a mat placed in the shallow basket, which forms the top of the table.”

A communist revolution seized Ethiopia in 1974, ultimately executing the emperor and bloodily ruling the country until 1991, and reporting from Ethiopia during this time tended to focus more on its political troubles than its cuisine.

“At Castelli’s Italian restaurant in downtown Addis Ababa,” began a 1977 Associated Press story from the country’s capital, where life went on, more or less, “diners pause momentarily over the lasagna and squid cooked in cream and garlic sauce to listen to the crackle of nearby gunfire. Then they continue eating and talking. It’s The Revolution.”

From a 1995 Associated Press article

Milwaukee readers got another spotty taste of Ethiopian food in 1978 when the Sentinel published a review of Laurens van der Post’s First Catch Your Eland, a book all about African cuisines.

“There were a variety of continental dishes,” critic Rich Gotshall writes, “but for every one there was a native dish. In addition to the finest French wines, there was tedj, an ancient Ethiopian mead, sweetened with honey as is much of Ethiopian food.” Gotshall also describes the breads, including one made of “slightly damp and roasted barley flour which can be rolled between the fingers into large pellets. It is swallowed with a native tea called thalla.”

Hard to say for sure here whether the mistakes here are Gotshall’s or van der Post’s: Ethiopians don’t use honey in a lot of their food, and t’alla is a beer, not a tea. As for the bread, it sounds like injera, although someone fails to mention that those “pellets” contain morsels of the various stews on the table.

I have a copy of van der Post’s 1970 book, African Cooking, where he writes tej, not tedj, and where he correctly calls talla (his spelling) a beer, not a tea. It’s unlikely he got it wrong in another book eight years later. He does say that Ethiopians use honey as a sweetener, but not that they use it in many dishes. It would be more than two decades before Milwaukeeans got their own Ethiopian restaurant and could find out for themselves.

Thanks to local resident Dot Hailey, Washington, D.C., readers of the city’s Afro-American newspaper learned about Ethiopian food in an unusual way: Hailey was a production publicist with Shaft in Africa, a sequel to the hit film Shaft with Richard Roundtree. The movie shot in Ethiopia, and Hailey wrote a series of articles from location in 1973.

Part one of her series chronicled their arrival in Ethiopia and meeting the emperor, and part three took them to Eritrea, where they met some camels. But in part two, she gives a thorough description of a meal, beginning with hand washing and featuring t’ej, “a powerful honey wine served in squat little bottles. As Richard held the bottle by its neck and tilted it back to drink, he got a round of applause. The prince was proud of him. T’ej is a wine to be drunk with gusto. It is made in Ethiopian homes and the taste varies.”

The host brings out some mesobs next, and Hailey is surprised to learn that they are the evening’s dinner tables. The injera, she says, is fermented for three days and cooked over a eucalyptus wood fire. She compared the texture to a Mexican flour tortilla.

Finally, there are the entrees. Doro wot is a spicy chicken dish made with berbere, “a tangy hot sauce used to season Ethiopian dishes, ” she explains, and gomen, “kin to the American collard greens,” was served with buttermilk (that is, ayib, the Ethiopian cheese). The meal also included another delicacy: “Richard wrapped a piece of kitfo and popped it into my mouth. It was raw meat.” That’s all she says, so we may never know if they got tapeworms from the experience (a possibility even now, let alone back then).

Click here to see a larger chart of the first Ethiopian restaurants around the world.

The Toronto Globe and Mail sent a reporter to Ethiopia in 1978, and he wrote about the food as though Toronto had never tasted it (the city had no Ethiopian restaurants then).

Robert Turnbull’s playful piece recalls the experience of his meals in Ethiopia, where

at each dining place sits a large, lidded basket with patterns of red, yellow and green. The moment diners are seated, a waiter in flowing white gown whisks the basket away.

Soon he returns with it in his arms. He puts it down and with a flourish lifts the lid, revealing injera, the unleavened bread of Ethiopia. A round of injera is a good two feet across, about half-an-inch thick, and looks like a disc of sponge rubber in biscuit brown shade. It is mild and surprisingly light.

Now you know. The basket is the table. The injera is the tablecloth to be eaten.

A dish of stew, pungent and blisteringly hot to the palate, comes to the table.

What’s this? I asked.

Wat, replied the Ethiopian.

I repeat the question. It’s wat. W-A-T, he says.

Now we know what’s wat, it comes to our table in portions of chicken wat, mutton wat, goat wat and beef wat.

Since there is no cutlery of any sort, the idea is to tear off a piece of the tablecloth – the injera – use it to scoop up some wat, then pop injera and all into the mouth.

The beverage accompanying the wat is tedj. Served in a glass flask it is a pleasant-tasting, refreshing drink, buttercup yellow in color, made of a mixture of honey, hops and water.

Wat a meal.

Some lucky residents of Hendersonville, N.C., got a chance to taste Ethiopian food decades before the state got its first restaurants: On Oct 23, 1978, the Times-Record announced that Sharon Smith, who spent seven years as a missionary in Ethiopia, “will supervise the preparation of a typical Ethiopian meal” at a local church. One can only wonder if the meal included t’ej.

AFTER BEYENE’S GUILILAT’S RESTAURANT in Long Beach disappeared, along with the fancier one he opened in San Diego in 1969, so did virtually all newspaper accounts of Ethiopian restaurants in America. If some of them opened during the next decade, almost nobody seemed to notice.

Three sentences in the Dec. 13, 1972, Miami News mention Ethiopian Lair, a new restaurant that offers a “typical” Ethiopian dinner (not described) for $7.50, although “Haile Selassie would be pleased,” the story says. This was another rare early restaurant before the boom of the late ’70s began. In Ann Arbor, Mich., that same year, a group hosted an benefit Ethiopian dinner (cost: $1.50), with proceeds going to famine relief.

No doubt many other such places opened and closed in the time Beyene’s restaurant in 1966 and the start of the nationwide boom in 1978, and newspapers probably missed a lot of them.

Six years before Ethiopian food arrived in Washington, D.C., Jim Hoagland did a story for The Washington Post about the difficulty of finding African restaurants in Africa, where people who dine out seek non-native cuisines. He says that while west African dishes are nicely spiced, most east African cuisine tends to be bland – with one exception.

Sewasew Hailemariam, an exchange student, cooks Ethiopian food for her American hosts in Los Angeles, 1967

“The intricate and highly spiced wot (stew) and zighini (curry) of Ethiopia can hold their own against most exotic dishes,” he wrote in 1972. “But few Ethiopians trust anyone outside their own homes to prepare the dishes to their liking, and they rarely patronize the few restaurants that specialize in the local cuisine. Aficionados of wot swear that the Hilton Hotel makes the best in Addis Ababa, but it has to be ordered 24 hours in advance.”

Ethiopian food finally staged its American cotillion in D.C. in 1978 with the opening of Mamma Desta, and the boom slowly began.

“You could say this place is unpretentious,” Robert L. Asher wrote in The Washington Post on May 22, 1978, “if you mean that from the outside it’s nothing more than a small yellow sign over a window that you can’t see in, on a block that doesn’t exactly dazzle.”

Asher encountered a few surprises: first, no menu – their hostess just described the dishes Desta Bairu had decided to make that day – and second, no silverware. He apparently knew nothing about the cuisine and its custom of eating with your hands using injera, which he describes as “flying-saucer-sized pancakes with a kind of foam rubber texture.”

He and his family (plus a friend of his son) ordered three meat dishes: tibs (mild beef), yebeg wot (spicy lamb), and the redoubtable doro wot, which he describes but doesn’t name: “The chicken was in a pot along with a lone hard-boiled egg, a nice touch that settled any long-standing debate about which came first.”

In the end, Asher and his companions ended up enjoying both the meal and the experience.

A month later, the Post’s restaurant critic, Phyllis Richman, reviewed the restaurant, and she liked it, although she mistakenly called it the country’s first Ethiopian restaurant. (There were at least three earlier ones: Long Beach in 1966, San Diego in 1969, Miami in 1972.) A year later, her August 1979 piece “Ethiopian Eating” began with news of the cuisine’s progress: “Rumor has it that there are only three Ethiopian restaurants outside of Ethiopia. The fact is that Washington has four of them.” She also found “two now-familiar Ethiopian dishes on an otherwise Middle Eastern and Italian menu” – a restaurant owned by Ethiopians, I’d guess – “and discovered that the new owners of the Peasant Basket were Ethiopian, and would prepare an entire Ethiopian dinner for a group on request.”

At last, Ethiopian food had found a hometown in America.

A meal at Tana in Dallas, 1994. The diners have individual plates in front of them but don’t seem to be using them.

The next year, Sheba opened in lower Manhattan, and The New York Times had a chance to introduce the cuisine to the city, calling the small restaurant “luncheonette-like.”

“If the polite and gentle personnel at Sheba Restaurant in TriBeCa have their way,” Mimi Sheraton wrote on Dec. 7, 1979, “New York can learn a whole new food vocabulary, one that includes words like berbere, doro wot, kitfo, alicha and injera.”

The staff taught people how to eat with injera, although the restaurant did offer forks to people who wanted them. Sheraton enjoyed several dishes: doro wot, tibs wot, alicha fitfit, and especially the kitfo, which she compares to steak tartare. For veggies, she had atkilt alicha (a mild mixed vegetable stew) and kik wot (spicy yellow peas). She didn’t care for the kekil merek (a beefy broth) and the minchet abish (chopped ground beef seasoned with fenugreek).

At the end of her piece, Sheraton notes that the restaurant also offers omelets and burgers. “But the real reason for making the trek to TriBeCa,” says the uptown critic, “is for the Ethiopian food.”

Imagine how the history of Ethiopian food in America might have changed in the 1970s if Herb Kaestner had ventured out of his Addis Ababa hotel room during a stop in Ethiopia.

At the time, Kaestner worked for McCormick, the spice company, and several times a year, he traveled the world looking for new spices to market in America. A profile of him in the Los Angeles Times on Nov. 15, 1979, says he was “trapped in an Ethiopian hotel room during the revolution.” That would have occurred around 1974. Had the streets of Addis been more hospitable, he might have discovered berbere a few years before Workinesh Spice Blends began to make it in America, and a decade before two Ethiopian-Americans formed NTS Enterprises in Oakland, Calif., and began to import spices from Ethiopia.

By the 1980s, more big American cities greeted their first Ethiopian restaurants, and the cities’ newspapers brought them to their communities.

Chicago got its first restaurant in 1984 with a familiar face in the kitchen: Desta Bairu, who was the cook and namesake at Mamma Desta’s in Washington, D.C. She left there, lived a few other places, and soon found her way to Chicago to become cook and co-owner of Mama Desta’s Red Sea (losing an “m” along the way). She sold her share of the restaurant after a few years, and her business partner, Tekle Gabriel, continued to operate it until its closing in 2009.

Here’s an unusual pop-up Ethiopian meal: In San Diego, in 1984, to celebrate the one-year anniversary of a city-financed center for homeless people, the Transient Center “served up alech, zigni, sambosa and injera to a shuffling line of street people and downtown business executives,” the San Diego Union reported. “The Ethiopian fare – spicy stews, vegetable dishes and unleavened bread – was part of a two-hour affair that included center ‘clients’ as well as downtown property owners and businessmen.”

Philadelphia had Ethiopian food by 1984, and on Feb. 26, the Philadelphia Inquirer reviewed Nyala, which sounded like the city’s first.

“Wots (stews) and kitfo (Ethiopian steak tartare) and tibs (tender beef cubes) and sambusas (appetizer pastries) are all on the menu of this new Ethiopian restaurant,” the story said, “and all four dishes (plus several others) are as unusual as the names might lead you to expect.”

A 1986 article by the Knight-Ridder news service visited Philadelphia’s Red Sea and its married owners, Kidane Teklu and Zeru Gezehegn. The story calls the cuisine “one of the world’s more exotic. It is spicy, hot, characteristically full-flavored, healthful, often intricate, and sometimes so subtle as to be almost fragile.” (That’s one of the more unusual ways of describing the food.) The story includes recipes for niter kibe, injera, berbere and doro wot.

And here’s a quick item from “Are Trendy Foods a High Risk,” a 1987 Washington Post story: “Eating steak tartare has always carried inherent risks, since bacteria in the meat would not be killed via cooking. Now a variation of the raw-beef dish, called kitfo, is being featured in Ethiopian restaurants.” This must have been before sushi invaded the American palate because the story never uses the word.

Hard to believe that a big diverse city like Montreal still has only two (down from three) Ethiopian restaurants. So imagine how exotic it must have been in 1983 with the opening of Addis, the city’s first.

“It’s a very strange feeling to attempt to write about a cuisine you know absolutely nothing about,” Montreal Gazette critic Helen Rochester began her piece, a review of “what I am sure is the city’s only Ethiopian restaurant. Few westerners are familiar with [African cuisines] and little has been written about them. It is still a dark, mysterious continent as far as its food is concerned.”

She consulted a book (Herbs and Spices by Waverley Root), had a meal, and passed along her learning.

“The menu is small and a little confusing to westerners as there are no beginnings and endings,” she writes, “just a list of main dishes based on chicken, lamb, beef or vegetables.” With some help from her server, she orders doro wot, siga wot, minchet abish, atkilt wot and misir wot – a very spicy combo. She explains injera and berbere, and she notes that except for the chicken, “most of the meats are ground and so spiced as to be unidentifiable.”

It seems Ethiopian restaurants came and went in Montreal back them, an indication that the city didn’t flock to the unknown cuisine. Two years later, Addis was closed, and in its place was La Mer Rouge, with Restaurant Ethiopie opening and closing in the interim.

Montreal Gazette critic Ashok Chandwani visited La Mer Rouge (“The Red Sea”) and wrote a well-observed story about this “piquant cuisine that seems to have an affinity for some Indian dishes in its use of certain spices” (sending him to review the place was a better choice than Rochester). He ordered the same dishes that she did, and he gave everything kudos for flavor except the doro wot, which he says “revealed no sense of actually having been simmered in the sauce covering it.”

That would be heresy in an Ethiopian kitchen, but Chandwani notes that the menu also offered a Senegalese chicken dish in peanut sauce, so he speculates that the cook makes the chicken separately and then applies the necessary sauce. If so, it’s no wonder La Mer Rouge no longer exists.

Portland’s first Ethiopian restaurant, Jarra’s, opened in 1983, and two years later, the Chronicle in Spokane, Wash., took a road trip to introduce its readers to the unusual cuisine. Located on a “dingy, industrial fringe of downtown, the inside is warm, funky and perfumed with spice,” Alice Feinstein reports. “You can choose from dishes with delightful names such as doro wot (chicken in hot spicy sauce, one of the best-selling items), zezil wot (sirloin tips in hot, spicy sauce), or minchet abish (ground beef in mild sauce).” These are all common dishes, although zezil should be zilzil.

The story then goes on to explain the use of injera and the fact that many dishes can be quite spicy because, owner Petros Jarra says, “we refuse to tone down for American taste.” He recommends that patrons who can’t stand the heat should simply order a milder dish. The story includes recipes for niter kibe, injera, berbere, doro wot and sik sik wot (a beef dish).

It all must have seemed quite exotic to residents of Spokane, which today has only one Ethiopian restaurant, Queen of Sheba, although large communities in Portland and especially Seattle are each about 300 miles away.

New York Times reporter Bill Keller wrote a piece on Ethiopian restaurants in the summer of 1984 that got wide circulation in newspapers across the country. It focuses on places in Washington, D.C., but includes information about the growth of the cuisine nationwide.

One of his sources, Keller writes, “counts four Ethiopian restaurants in New York, five or six in Los Angeles, four in Oakland, California, and two or three in Dallas. But Washington is the capital of the movement.” The story then describes, concisely and accurately, such things as doro wot, kitfo, injera and t’ej. Keller also notes that many Ethiopian restaurants serve some Italian cuisine, “a relic of the days when Italy colonized that corner of Africa.”

Seifu Lessanwork opened Blue Nile in Detroit’s downtown Greektown neighborhood in 1985 and then another Blue Nile soon after in Ann Arbor. The original restaurant is now in suburban Ferndale, and the two restaurants are among the oldest in the country, especially after the closing of Seattle’s first Ethiopian restaurant, Kokeb (1982-2012), and Portland’s first, Jarra’s (1983-2014). The oldest now is Meskerem in Washington, D.C., opened in 1984 by the people who still own it.

Seifu made the newspaper in an unusual way in 1987 when he instituted a “smoking surcharge” at his Detroit restaurant. Patrons had to put 25 cents into a piggy bank for the first cigarette they lit up and 30 cents for every one after that. But if there was a pregnant woman in the room, the fees rose to 50 and 75 cents. He donated the money to the American Lung Association.

Jarra’s in Portland, 1983-2014

“When a restaurant has a smoking a section and a non-smoking section,” Seifu told the Associated Press, “patrons really end up breathing the same air, and the problem is always resolved in favor of the smoker.” He added that he hoped the way of eating Ethiopian food – with your fingers – would dissuade people from smoking.

In the midst of this spurt in Ethiopian restaurants, Christian Science Monitor reporter David K. Willis visited Ethiopia and filed a June 1985 story all about teff, the gluten-free grain used to make injera.

His guide, Mamo Mulat, an agriculture official with the federal government, thrusts a hand into a pile of teff to show him what it looks like.

“On Mamo’s palm lay a small pile of tiny, grayish, nondescript seeds, almost like grass seeds,” Willis writes. “One puff and they would blow away. From this seemingly fragile grain, which is grown almost nowhere else in Africa, Ethiopians make the staple of their national dish called injera: a soft, pliable, slightly fermented dough that is served folded like a napkin. You pull a piece off and dip into into pungent, spicy sauce.”

The piece, which appeared in newspapers around the country, goes on to describe the challenges of growing teff and the damage to the crop done by the country’s drought, but it’s more about the culture’s attachment to teff than the grain itself.

One month later, the Associated Press wrote a story about a United Nations program to help Ethiopians grow more teff more efficiently. But where the Monitor story claims that the temperamental crop “requires rain at precise points during a short growing cycle of 90 days,” the AP story calls it “drought resistant” and able to grow on rough terrain. The latter is more accurate: It’s so resilient that Yemenis call it the “lazy man’s crop.” But even teff needs some water, and a devastating Ethiopian drought can destroy a field of it.

Ethiopian restaurants got a quick mention in a 1988 Associated Press story about a professor at Penn State who researched America’s favorite ethnic cuisines.

Not surprisingly, Chinese topped the list, with Italian second. But the professor also “found no strong correlation between ethnic restaurants and the preference of specific ethnic groups except for some smaller cuisines such as Ukrainian, Polish, Basque, Thai, Afghan, Ethiopian and Filipino.” In other words, when Ethiopians in America back then went to a restaurant, it was an Ethiopian one. The story lists the number of restaurants he counted in the United States for many cuisines, from 7,796 Chinese to seven Hawaiian. Ethiopian restaurants didn’t make that list, although Washington, D.C., alone had more than seven at the time.

A 1988 squib in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette began, “Move over, oat bran. That current nutrition craze – and a lot of other grains – may soon become outclassed by something called teff.” The story cites two advantages of teff: It’s very nutritious, and it’s resistant to drought. “You might say it is the teff-lon of the grain world,” the story quips. It also notes that an American man, Wayne Carlson, grows teff on 200 hundred acres of land in Idaho.

The Associated Press did a story on American-grown teff in 1991 that focused on Carlson, who had been to Ethiopia in the 1970s and concluded that the soil and climate of his native Idaho would grow hearty teff. He launched The Teff Co. in 1984, and by the early ‘90s, he had donated 25,000 tons of teff seeds to drought-ravaged Ethiopians, who were surprised to learn that their ancient grain was being grown in America.

The AP story visited Carlson at his Caldwell, Idaho, farm, where he talked about his enterprise. His customers by then included many Ethiopian-Americans and Ethiopian restaurants that wanted teff to make injera like back home. Before Carlson and others – including Workinesh Spice Blends – made teff more available in the United States, Ethiopians would use a mix of wheat and barley flour to make injera. Even today, though, because teff is more expensive than other grains, most restaurants here mix it with wheat, although more and more, some restaurants have begun to offer pure-teff injera to meet gluten-free needs.

Iris Krasnow of UPI wrote a piece in 1985 for which she talked to Ethiopian restaurateurs in Washington, Dallas, Chicago, San Francisco and New York in a story that surely made more people aware of this emerging cuisine, along with some social attitudes toward it.

“Meat stews and vegetable dishes spiced with hot pepper, cardamom, turmeric, cloves, ginger and thyme are heaped in separate clumps on a large pizza-style pan covered with a thin, spongy pan cake called injera,” she writes. The ingredients certainly sound tasty, although the image of “clumps” doesn’t exactly entice. She then explains the absence of silverware and the use of small pieces of injera “to make sloppy finger sandwiches.”

And she had a suggestion: “Dolled up couples out on their first date should think twice about eating Ethiopian. Dishes like yedoro wot (chicken smothered in hot pepper paste), zilzil tibs (beef sauteed with butter and onions), zemamoojat (collard greens melded with cottage cheese) and yemisir wot (pureed red lentils) tend to be messy.” Zemamoojat is a dish that comes from Ethiopia’s Gurage culture, which gave kitfo to the national cuisine.

“The food is hearty, spicy, exotic,” Dallas writer Steven Reddicliffe told Krasnow. “It’s everything yuppies want.” As if to confirm his observation, Washington lawyer Nancy Hertel says, “After years of elegant sushi and perfect little pâtés, I love the lack of sophistication.”

Some of the restaurant owners said people feel guilty about eating Ethiopian food with so much famine back in the homeland. But one said that Ethiopians need the income now more than ever so they can send some back home to needy family members.

The Christian Science Monitor spread some good news about Ethiopian food – or “food from the dark continent,” as the headline says – with a 1988 story asking: Will it be America’s new ethnic food fad?

The piece calls injera “the cornerstone” of the cuisine and says, “The most dramatic feature about injera is that it replaces eating utensils.” Reporting from Boston, the writer talked with Nega Mesfin, the owner of Ethiopian Restaurant (now gone). He explains all of the basics, and we even get a peek into the kitchen during the making of injera.

Winnipeg, Manitoba, got its first Ethiopian restaurant in 1990, but the year before, in the city’s daily Free Press, readers got a rich lesson in Eritrean cuisine, which is the same thing, just with Tigrinya names for many of the dishes.

The story revolved around Eritreans living in Winnipeg, and for several detailed paragraphs, they talked about “a traditional Eritrean meal for Christmas dinner” that includes injera topped with zigni (or wot in Amharic), “a meat stew made with hot peppers,” as well as vegetable dishes. “Zigni is made with beef or mutton in Winnipeg,” the story says, “but it is traditionally made with the red meat of a goat in Eritrea. The goat’s stomach is used to make an extremely hot stew and is also eaten with injera.”

Himbasha (or ambasha) is a special leavened bread “much like a soft fluffy pizza crust,” made with flour and a touch of sugar. “Eritreans do not eat sweet food,” the story goes on, “although very sweet tea, spiced with cloves and served in glasses, is almost the national drink.”

One thing the Eritreans missed was suwa (t’alla in Amharic), “a spicy, potent beer for special occasions [that] few people in Winnipeg make because it can be a complicated process and many of the ingredients are not available here. But [they do] duplicate another traditional drink in Winnipeg by mixing honey with water, raisins, yeast and Tang, and letting the mixture ferment for three weeks.” This sounds like a diaspora version of t’ej in a place where gesho was probably impossible to get.

Ethiopian cuisine had reached Texas by the early 1980s, and in 1989, Waltrina Stovall of the Dallas Morning News visited River Nile. “The marquee out front depicts the universal symbol for ‘no’ over a knife and fork,” she wrote, putting this new cuisine into context. “The folks at River Nile mean it, too: No silverware is handed out. In the Ethiopian manner, you eat with your fingers. The dining technique – bits of food are wrapped in spongy injera bread – is not all that different from fajita manuevers. And Tex-Mex-trained diners also should take to the spiciness of Ethiopian food.”

Three years later, in another piece for her newspaper, Stovall wrote that “Dallas has had restaurants featuring Ethiopian food for a dozen years or so, yet many diners have never tried the fare, perhaps fearing it is ‘too exotic.’ Actually, Ethiopian food has several aspects that seem downright Texan. One, it is spicy. Sometimes blisteringly so. Raw jalapeño peppers are used with abandon, along with a searing spice-pepper blend called berbere.”

This 1992 piece claims that Dallas had Ethiopian restaurants “for a dozen years or so.” If it did, the Morning News made no mention of them until the late 1980s. There were, however, a few stories in 1971 about the cuisine that described “injera, an excellent moist bread, and various kinds of wots, or stews,” as well as t’ej, a wine made of fermented honey.”

This 1970s-era luggage tag from Ethiopian Airlines

depicts the European food served on international flight

But in the 1980s, just as more and more restaurants began to open around the country, another story about Ethiopian food emerged: The Ethiopian famine of 1983 to 1985 would claim more than 400,000 lives and lead to many headlines and worldwide relief efforts.

These stories about the famine reminded people that not everyone in Ethiopia eats what we’ve come to know as the “national cuisine.” Some Ethiopian-American restaurant owners at the time donated some of their profits to the effort, and a syndicated political cartoonist, Ed Stein, drew a panel in 1984 depicting an empty bowl and a message asking people to contribute to the relief. He raised more than $5,000 in one day.

The legendary muckraking journalist Jack Anderson published a squib in his Washington Merry-Go-Round column on Feb. 5, 1985, about a drop in business at an Ethiopian restaurant in D.C. because famine reports made customers “nervous,” an unnamed restaurant owner said. Another owner donated $1,000, a full night of receipts, to famine relief. Anderson also noted a winery in Canada that made t’ej and imported it to the U.S. That was probably Gondar Tej, made by the now-defunct London (Ontario) Winery.

And also in 1985, a review of an Ethiopian restaurant in the West Side Spirit, a New York weekly, proffered this: “The Mexican craze may have peaked, and Ethiopian food may well be the next big fad.” We’re still waiting for that to come true.

Several Ethiopian restaurant owners have told me that they rarely have African-American customers, and they don’t understand why. So it was good to find a story from Newburgh, in upstate New York, about the Ebenezer Baptist Church, which in 1990 “sought to reclaim a heritage lost for centuries.”

The members of the church organized a dinner that revolved around African cuisines, and the menu included three Ethiopian dishes: misir wot (spicy red lentils), zigini (spicy beef stew) and injera. The story in the The Evening News also mentions berbere as the spice used in the stews, but it doesn’t say whether the church actually had any.

By the 1990s, more big cities, and even some smaller ones, began to have Ethiopian restaurants, and newspaper stories became more frequent. Even The Joy of Cooking, first issued in 1931, got around to including an Ethiopian recipe in its 1997 revision: It was the redoubtable doro wot, and it even included the preparation of berbere, albeit with paprika, a common ingredient in commercially made berbere today.

Lancaster, Pa., in the heart of Amish and Mennonite country, welcomed Ethiopian food in 1991 with the opening of Blue Nile. “We want to make it as unique and authentic as we can,” Mamo Dula told the Lancaster New Era. He moved to Lancaster after marrying a Mennonite missionary from the city – the area now has an Ethiopian population of about 400 people – and while his place is gone, Lancaster has the new restaurant Addisu.

For a Kwanzaa celebration in Fredricksburg, Va., in 1993, a local group planned a meal of dishes from African cultures prepared with a Southern twist, and the Free Lance-Star wrote about it. The Ethiopian contribution, taken from the book Cooking the East African Way, was luku – stewed chicken with hard-boiled eggs.

This familiar dish is called doro wot in Amharic. Luku is the word for chicken in Afaan Oromo, a widely spoken language in Ethiopia, although it’s unusual that the cookbook simply uses the word for chicken to name this dish – and to simplify its spelling from the proper lukkuu. The full name for doro wot in Afaan Oromo is kochee lukkuu or kochee handaanqoo. Lukkuu and handaanqoo mean chicken in different dialects of the language, and kochee is wot (spicy stew).

In 1995, AP writer Dana Jacobi wrote a story that described the basics and presented recipes for niter kibe, berbere, doro wot and tikil gomen (cabbage and carrot stew); and a 2008 story by J.M. Hirsch was all about doro wot (including an “adapted” recipe). These stories appeared in newspapers from Maine to Alabama to Michigan – and no doubt many points even further west.

Fourth and fifth graders at Holy Trinity Lutheran School in Bowling Green, Ky., learned about Ethiopia in 1995 and collected school supplies to send to children in the drought-stricken country. They also got a taste of the cuisine.

“The cafeteria treated them to Ethiopian stew with cabbage, potatoes, tomatoes, other vegetables, meat and spices,” the Daily News reported. “Not all students were as open to finding out about the unusual meal as they have been about the country’s other attributes. Some students complained of stomach aches after eating the Ethiopian stew.”

If residents of Lawrence, Kan., didn’t read the revised Joy of Cooking, they could have learned about Ethiopian food from an article in the April 23, 1997, issue of the Journal-World. The town had no Ethiopian restaurant – the state now has just one, in Overland Park – but Lawrence residents Myles Schachter and Rhonda Ross had tasted the food in other cities and talked to their town newspaper about it.

The story describes the food well and recounts Schachter’s attempt to recreate it at home. He spent eight years searching for one spice – it turned out to be nech azmud, also called ajowan or bishop’s weed, a white Ethiopian cumin – and he got some at a market in D.C. They hosted an Ethiopian dinner for friends, serving minchet wot (with lamb and goat rather than the traditional beef), gomen, ayib, misir wot and atkilt alicha (with cabbage and potatoes). They were an adventuresome culinary couple, and the residents of Lawrence got a solid lesson on the cuisine.

Gainesville, Fla., still has no Ethiopian restaurant, but a big feature story in the March 2, 2000, edition of the Gainesville Sun presented the cuisine along with recipes for fasolia, gomen, doro wot, berbere and niter kibe. “Family members can feed one another,” the headline said, “and a host may also feed his or her guests the first bite.” The headline refers to gursha but never mentions the term.

The story revolves around two local women – one Ethiopian, one American – who became friends and cooked Ethiopian food together using spices from Ethiopia. And on Thursday nights in Gainesville, in the Book Lover’s Cafe, a chef prepared a four-course Ethiopian meal served on injera.

A 2002 Washington Post story about injera got wide circulation in syndication around the country – for example, in the Observer of Fayetteville, N.C.

“Take the mingled aroma of molasses and yeast,” Walter Nicholls’ piece began. “Add the nutty essence of an exotic grain. Mix well. It’s injera, the Ethiopian staple – a soft and porous flat bread that serves as a centerpiece of Ethiopian cuisine.”

His story goes on to talk about the many markets and bakeries in Ethiopia that make injera, and he describes how to use it to eat.

A 2005 Associated Press story, again widely circulated, focused on the growing Ethiopian community in Washington, D.C., with some talk of food: “Patrons use their fingers – no forks here – to tear into spongy pancakes and scoop up exotic cuisine such as awaze tibs, which is lamb marinated in jalapeño, tomato and garlic.”

Sarasota, Fla., got its first restaurant in 2005 with the opening of Fly, and the critic who reviewed it had mixed feelings: She liked a lot of the food but not the service. The menu was quite diverse, offering such rarely seen items as sinig (a stuffed jalapeño pepper) and helbet (a shiro-like legume puree). Fly is gone now, but Sarasota has Queen of Sheba to replace it.

And here’s an interesting twist on Ethiopian cuisine in Sarasota: Maximo, which bills itself as an Italian and South African restaurant, uses berbere in several of its dishes. The Sarasota Herald-Tribune did a squib describing some of them: You’ll find it spicing up garlic and butter shrimp, tuna with creme sauce, a lamb shank, and even some straight-up Ethiopian zigini (a beef stew).

FINALLY, THERE’S PITTSBURGH, MY HOMETOWN, which arrived late at the table, and for a while, some confusion reigned.

The Pittsburgh Gazette of Aug. 5, 1868, informed its readers that “since the Abyssinian expedition, raw beef dressed in pepper and mustard has become a fashionable dish in England.” It’s buried deep in a column of one-liners (“ephemeris”) from around the world. People who read stories that year about Britain’s military foray into Ethiopia would understand the reference.

The city got a rare early sip of t’ej in a 1955 news wire story about the way diplomats in Washington, D.C., tend to over-imbibe.

“The eye-opening mixture offered at the Ethiopian embassy topped everything,” the glorified gossip columnists wrote. “A sweet-tasting brew known as ‘mead’ is made of honey, barley and Ethiopian hops. It’s one of the most powerful drinks in the world and dates back to biblical times. After a few gulps, several of the guests weren’t quite sure what century they were in.”

The writers’ naivete almost makes it sound like “mead” existed nowhere else in the world, and they never use the name t’ej. Perhaps they were teetotalers, which could explain why they’re bad journalists. The party also featured mulmul, described as “spicy minced meat rolled in a thin bread.” In fact, mulmul is a type of Ethiopian bread, so the writers may have misunderstood what their source told them (or else they’d enjoyed too much t’ej).

Pittsburgh got its next Ethiopian meal in 1980 at an eclectic restaurant called Born Free, which prepared some African dishes. The Ethiopian entry was an appetizer of tere siga, raw beef cubes with a sauce that had “the texture but not the taste of chutney,” the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette food critic reported. He then described the sauce, “a combination of two sauces of African origin: niter kibe and beri-beri, we were informed. And it was apparent that ginger root, paprika and assorted chilis went into the preparation.”

Close enough: Niter kibe is clarified spiced butter, not a “sauce,” and of course, it’s called berbere, although who knows whether it was domestically assembled or imported from Ethiopia. And neither is quite so broadly of “African origin.” They’re pure Ethiopia.

The Pittsburgh Press – the city’s larger daily before its demise in the 1992 – published a story on June 30, 1985, that got things embarrassingly wrong. The centerpiece of the story was Martha Russell, a resident of the nearby small town of Ford City, whose son married an Ethiopian woman when he was stationed in Africa with the Army. Two of her grandchildren were born in Ethiopia, and when the family came to America, the children were suffering from malnutrition.

“The problem then and now in the country,” the story says, “is a diet made up primarily of three items: a poi-like substance cooked like grits; angeta, a very hot and spicy beef mixture; and zigni, a pancake-like bread cooked on the stove.”

Of course, those last two items are flip-flopped: injera (not angeta) is the bread, and zigni is the spicy beef dish. I’d guess that the grits are probably a porridge, like genfo or qinche. So this was a pretty bad introduction to Ethiopian cuisine for Pittsburgh.

The Knight-Ridder news service wrote a story in 1991 about the spices used by different cultures to heat up their food, and the Beaver County Times, not far from Pittsburgh, published the story, which describes berbere: “It’s a blend of garlic, red pepper, cardamom, coriander, fenugreek and more. Pronounced bear-BEAR.” Except for the pronunciation, that’s pretty much right. The next year, another Knight-Ridder story rounded up the many variations of chicken soup that cultures around the world use for (psychological) healing purposes: Ethiopia’s yedoro shorba (literally, “chicken soup”) got a mention.

As if to make up for its earlier error, The Pittsburgh Press published a pair of feature stories in 1992 about Mimi Stutz, a city chef tasked with the challenging of creating African-themed hors d’oeuvres for a reception to welcome a group of African diplomats.

Her Ethiopian offering was dabo kolo, little pieces of fried dough served as a snack on which to munch. Ethiopian cuisine doesn’t traditionally have appetizers or hors d’oeuvres, and while Stutz spiced up her dabo kolo with berbere and dusted it with sugar, it still doesn’t sound as tasty or exotic as her Tunisian salsa meshwiya.

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette columnist Diana Nelson Jones took a trip to New York City in 2000, staying with friends and having dinner with them at Awash, an Ethiopian restaurant in Manhattan.

“It is here where I ate ground meat – raw, seasoned sirloin – for the first time,” she wrote, “and where everyone at the table reaches his spongy piece of bread toward a communal platter, pinching bites of beet root, carrot, chickpea, lentils and collards.” Later, she recalls “the moment at dinner when 13-year-old Ben, trying to pinch bites from his dense bowl of barbecued beef, says, ‘It would be a lot easier if we had forks.’ I hear delight in his father’s chuckle and response, ‘Yes, Ben, it would be easier.’”

It’s an amusing anecdotes, although the beef was not barbecued.

By the late 1990s in Pittsburgh, you could find doro wot, a popular dish at the fusion restaurant Road to Karakash, where you could eat it sitting at “an Ethiopian short table.” But we didn’t get our first full Ethiopian restaurant until 2004, when Jamie Wallace, a young corporate attorney, fulfilled his dream and opened Abay. It was an instant hit.

“For years,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette columnist Tony Norman wrote, “I’ve harangued friends, acquaintances and anyone who would listen about the fact that Pittsburgh could never consider itself an ‘international’ city until it had an Ethiopian restaurant. When Abay opens its doors to the public for the first time today, Pittsburgh will have officially entered a new age of gastronomical delight. It goes without saying that Abay is the only Ethiopian restaurant in Western Pennsylvania.”

He was right at the time, but in 2008, Pittsburgh resident and Ethiopia native Seifu Haileyesus opened Tana a few blocks from Abay, and suddenly, Pittsburgh had an Ethiopian food boom. It didn’t last long: Wallace closed Abay in 2013, weary of the breakneck restaurant business, and Pittsburgh relapsed to one restaurant. So we’re counting our blessings, albeit on one finger. And we’re still better off than those 10 states whose residents are waiting for news of their first.

Harry Kloman

University of Pittsburgh

anderson

Leave a comment