FROM HER KITCHEN IN FRANKFURT, GERMANY, Wilhelmine Stordiau has given some new twists to the idea of Ethiopian diaspora cuisine.

When people leave their native countries and migrate to new ones, they naturally take with them a love of their mother’s (or father’s) home cooking. Just as often, they go into the restaurant business. That’s how the world first got to taste Hunan chicken, pad thai, tandoori chicken, borsht, phở, hummus, sushi, baklava and strudel.

But for a variety of reasons – perhaps to please foreign palates, or because cooks can’t find the right ingredients, or just because traditions get lost – the cuisine of a diaspora sometimes doesn’t taste quite like it does back home.

Wilma Stordiau was born in Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital, and she’s one-eighth Ethiopian (she has an Ethiopian great-grandmother). She lived in Ethiopia until about the age of 18.

Then, in February 1975, after four generations in Africa, her immediate family moved to Europe to get away from the brutality of Ethiopia’s new communist dictatorship. She learned German, married a German man, settled in Frankfurt, raised a family, and worked in business and industry.

Eventually, though, she did more than just preserve her memories of the Ethiopian culture and cuisine she had come to cherish as a girl. She decided to make a living of it.

Six years ago, Wilma launched Begena Tedj, a company that now makes three varieties of the Ethiopian honey wine t’ej as well as katikala, a grain alcohol that you might call the Ethiopian vodka. (“Tedj” is the German way of spelling the word.) She sells her potent potables all over Europe and in Canada, and she’s traveled the continent to build her business.

Wilma bottled her first small batch of Begena Tedj in 2009 after two years of testing recipes, adapted from her grandmother’s recipe back home, until she found one that satisfied her. She pondered many names for her product and finally settled on Begena, the most prized string instrument in native Ethiopian music – just like t’ej is the most prized drink.

Along with being a winemaker, Wilma is an accomplished chef across a variety of cultures. But it’s her Ethiopian cooking that especially delights. And I don’t just mean the doro wot, kik alicha, shiro, fasolia and other dishes – familiar to us all from Ethiopian restaurants – that she prepares for festivals around Europe.

The writer Todd Kliman traveled to Addis Ababa recently and wrote a piece for Washingtonian magazine called “Can Ethiopian Cuisine Become Modern?” Perhaps Wilma has answered his question. She has a tremendous culinary imagination, and using the basic elements and foods of the Ethiopian table, she’s put them together to create diaspora cuisine unlike anything you’ll find in a restaurant.

Wilma simply calls her creations “fusion cooking” or “bridging” (Brückenschlag in German). “I think of the recipes as just guidelines,” Wilma says, “something like Denkanstoss – impulse to creation.” That means you can tweak some of the ingredients and preparations if you’re a skilled chef, or you can just trust the expert and do what she instructs. The dishes often don’t have their own special names, and Wilma usually describes them using their constituent ingredients. So just think of Shakespeare, and what he taught us about the rose.

BEFORE WE GET TO THE RECIPES, we need to talk about onions. “The ABC of the Ethiopian cuisine are the onions,” Wilma says. “When your onions are well made, your dishes cannot be bad.” That’s true of a traditional Ethiopian wot (stew), which revolves around kulet, a thick onion sauce spiced with berbere.

Not all of Wilma’s fusion dishes call for onions, and for the ones that do, it’s not always spicy onions prepared in a kulet. Sometimes, you just want plain chopped onions simmered in oil or butter. So here’s a recipe for making Wilma’s version of kulet. If a recipe calls for plain onions, follow this preparation, but don’t use berbere. Always use red onions in your recipes if you can. Ethiopians in Africa prefer shallots, and you can use them as well, although because they’re small, it takes more time to peel a lot of them before you chop them.

♦ Kulet (Spicy Chopped Onions). Begin by chopping the onions very finely (I cheat and use a food processor). Then, cook them at first in a dry pot without water, adding water little by little after a while to keep them from drying out. “When the onions are well done and transparent,” Wilma says, “add the fat (butter or oil), then add the berbere. Add some water and let it cook until you prepare the other ingredients.” And keep an eye on it, making sure not to let it dry out. You want it to be thick but not a paste.

The fat in her recipe can be niter kibe (Ethiopian spiced clarified butter), or perhaps Indian ghee (clarified butter, but without spices), or vegetable oil if you like (Wilma prefers canola, I prefer olive). You can add this to taste, as rich and “fatty” as you want it to be. Just don’t overdo it. The same goes for the berbere: Make it as spicy as you or your guests can handle. And you can make this in very large quantities, freezing it in portions that you’ll need when you cook. It’s not unheard of to chop 10 or 20 pounds of onions to make a big pot of kulet. If you use, say, five pounds of onions, then three or four tablespoons of fat and one or two tablespoons of berbere will make it spicy and rich without going overboard.

There are two more staples that pop up in a few recipes, so let’s learn how to prepare them.

♦ Awaze (Spicy Simmer Sauce). Using one tablespoon of berbere, blend in three tablespoons of water and one tablespoon of oil. You can make a version called deleh with three tablespoons of t’ej (or other wine) and one tablespoon of oil. Increase the ingredients proportionally for larger quantities, depending upon what the recipe demands.

You’ll need awaze in some of the recipes that follow. But you can also improvise, using it (or berbere) to spice up any dish you make in the cuisine of any culture.

♦ Fitfit (Injera “dough”). As everyone surely knows, Ethiopians don’t use cutlery to eat: They grab their food with injera, a spongy sourdough flatbread. It’s challenging to make at home, so for the recipes that demand it, plan on getting yours at an Ethiopian market.

Fitfit is chopped injera mixed with or into something. In Wilma’s dessert recipes, you’ll need to give the injera a dough-like consistency by mixing it with the liquid that each recipe demands.

“Fitfit should not be too dry but should also not be too moist,” Wilma says, so it’ll require some instinct on your part. You want your fitfit to be moist enough to mold into a dough-like ingredient that you can later cut into slices that hold their texture. So add the required liquid a little at a time to get the result that you need. In fact, Wilma recommends using old injera to make fitfit because it’s lost some of its fresh-baked moisture and can take on more of the flavor of the liquid you’re blending into it.

That’s it for the preliminaries, although there’s one more quick matter: Wilma loves garlic, and she recommends that you can use it to give “a fine touch” to any dish.

Now, let’s cook.

HERE ARE SOME OF WILMA’S UNIQUE RECIPES, most of which require at least one ingredient that you’ll need to buy at an Ethiopian market.

♦ Dirkosh with Shiro. This is a dish made by combining these two items: dried injera (although you can also use fresh injera) and pea powder.

You begin by making the shiro in the quantity of your choosing, depending upon how many you want to serve. For every half cup of water, add one tablespoon of shiro powder, which you can buy at an Ethiopian market, and cook it in a pot at a gentle boil until it begins to thicken. For the purpose of this dish, you want the shiro to be feses (thin) rather than doke (thick).

When it’s ready, let it cool until it’s just warm rather than piping hot. Then, add the dirkosh (or fresh injera) and mix it up, using as much as you need to absorb the shiro. (You don’t want it to be “too shiro-y,” Wilma says.) Put the mixture in a square container (like you’re making a cake) and press it a bit so it won’t fall apart later when you cut it. Cover it with a cloth, let it stand and cool, and when it’s cool, put a film on it and let it stand over night. The next day, cut it into squares and add some garnishes – Wilma uses chopped or shredded chilis, tomatoes, parsley and chives. (See photo above.)

♦ Meatballs. In any quantity you like, mix (by weight) two-thirds ground beef and one third fine bulgur. To taste, add salt, black pepper, and a touch of cinnamon and ground garlic. Mix well. Form small balls and drop the balls into boiling saltwater – or, if you like them crispy, pan fry them in hot vegetable oil. Serve cold or warm with a dip of your choosing: awaze, deleh, plain yogurt, or even yogurt with garlic.

♦ Spicy Yogurt Dip. Some of Wilma’s ancestors are Armenian, and she calls this recipe an Armenian-Ethiopian fusion. It’s a great way to spice up your yogurt.

Put a piece of cheesecloth over a container and pour one kilogram (about two pounds) of yogurt in it, then let it drain overnight. (Wilma uses 10 percent Greek yogurt.) Put the drained yogurt in a bowl, add three tablespoons of olive oil, three teaspoons of berbere, and a touch of salt (you can adjust the berbere to your desired spice level). Mix until it’s smooth and creamy. You can serve this mousse with raw vegetables (carrots or celery or anything), tacos or chips, including dirkosh (injera chips), or even matzos. And Wilma adds: “The water of the yogurt can be used to clean the face. It is fantastic against comedones (blackheads).”

“You can use this recipe to make lots of different tasty dips,” Wilma says. “Instead of berbere, you take minced rue, tarragon, thyme, sage. You can use one type at the time or you can mix two or three different ones. Garlic is also very good. When you do the yogurt with the herbs, you have to blend the herbs in a mixer with salt and the oil.”

♦ Spaghetti all’ Arrabbiata. Prepare 1.5 cups of finely chopped plain onions, not the spicy kulet variety, but just before adding the butter or oil, add some bacon cut into small cubes. (You may not even need butter or oil if the bacon provides enough fat.) Then, add one tablespoon of salsa and one tablespoon of berbere, blending the ingredients well and letting them cook “until you are afraid that it will burn,” Wilma says. Next, add one can of tomato puree and one can (14 ounces) of cut tomatoes. Finally, add a cup of cut green olives, one-half cup of minced parsley, one or two cloves of garlic, and one or two bay leaves.

Let everything cook for 45 minutes or so over a medium heat to let the ingredients and flavors blend – “as long as possible,” Wilma says, because “sauces are always tastier when they cook long.” Add some salt if needed, and you can add sprinkle fresh oregano on top before serving, but don’t cook it with the oregano. Pour the finished sauce over your favorite pasta.

“Any kind of noodles can be served with real Ethiopian food and tastes fantastic,” Wilma says. “You have often noodles served on injera in Ethiopia, especially spaghetti. I would say that they have become part of the Ethiopian cuisine.”

♦ Penne with Minchet Abish. This is perhaps the most “Ethiopian” of Wilma’s fusion cooking: It’s pasta topped with a traditional beef dish that’s sort of like an Ethiopian sloppy Joe. The pasta part is easy, so here’s how you make the minchet abish.

Chop three large onions and prepare them as described above in the plain variation (not kulet), adding a tablespoon of crushed or chopped garlic, and a half teaspoon of fenugreek (abish in Amharic). Cook this in the fat (niter kibe or oil) until the onions begin to brown. Add two tablespoons of berbere (or less, to taste) and a little water as needed to keep it from becoming too dry. Now, add one pound (one half kilogram) of ground beef and cook it all until the beef is done. Finally, add a quarter teaspoon each of cardamon and ginger, and a pinch of nutmeg (these spices are, more or less, what you call mekelesha in Amharic). Stir the ingredients and serve over penne (or other pasta).

♦ Shrimp Wot. Prepare 150 grams (about one cup) of spicy onions (see above). Wash and drain 500 grams (one-half pound) of shrimp. Add the shrimp to the prepared onions, bring it to a boil, then turn off the heat. Let it stand for a few minutes before serving. Wilma says that frozen shrimp works just as well as fresh shrimp if you defrost them overnight in the refrigerator. You can also make this dish with calamari or a fish of your choosing.

♦ Ye’shiro Shorba. This is Amharic for “shiro soup.” But shiro is a powder made of seasoned chick peas or peas, so in a way, this is an Ethio-fusion version of pea soup. Ethiopians make different types of shorba, and you’ll find restaurants that serve shorba made of lentil, chicken, lamb and the likes. But I’ve seen some other creative “Ethiopian” soups out there, like chicken and butter bean shorba, tomato and lentil shorba, pepper pot shorba, or just a good old vegetable shorba.

To make Wilma’s ye’shiro shorba, mix the shiro (2.5 ounces, or 70 grams) with a little bit of water so that it doesn’t clump, and then add the rest of the water (25 ounces, or 750 milliliters in all). Gently boil it on the stove until it begins to thicken, but don’t let it get too thick. Add three cloves of garlic, two chilis, some vegetable oil (2 ounces, or 70 milliliters) and four potatoes, cut into small pieces. Cook it for about 10 minutes, and when the potatoes are done, cut a strip of sausage into bite-sized pieces and add them to the shorba. You can add a little water at any time if it begins to thicken too much. Add salt if you think the sausage doesn’t make it salty enough. When the potatoes and sausage are cooked, discard the chilis, add a dollop of crème fraîche on top, and serve. This will make four to six servings. You can include some injera, dirkosh or croutons on the side if you like.

♦ Berbere Deviled Eggs. Here’s a spicy twist on a party favorite. Hard boil some eggs, as many as you like, and cut them in half. Put the yolks in a bowl and blend in some canned tuna, add berbere and lime to taste, and a touch of ginger if you like it. Mix the ingredients and fill the halved egg whites. If the mixture is too dry, you can add a pinch of mayonnaise.

♦ Goulash with Dumplings. This is perhaps the most elaborate recipe we’ll offer – Wilma’s take on goulash, prepared with Ethiopian spices, and with a side of homemade dumplings (they’ll look a little like gnocchi).

Begin with 250 grams (about 1.5 cups) of plain onions (not the spicy kulet type), add 1.5 tablespoons of margarine, then four pounds (about two kilograms) or beef stew meat cut into bite-sized chunks. You can add two or three cloves of garlic if you like as well.

Sprinkle in three tablespoons of awaze and one heaping tablespoon of berbere (or less if you don’t want it quite as spicy). Let it cook for about 10 minutes, stirring and adding a little water if it gets too dry. Then let it cook for about 30 minutes more, again adding bits of water as necessary to keep it moist.

Finally, add half a pound (500 grams) of sauerkraut (homemade or prepared), one teaspoon of caraway and two or three ounces of t’ej or red wine. Let it cook for another 30 minutes. Be sure you have some sauce for the dumplings.

Now it’s time for the noodles. Boil a large pot of water. Mix half a pound (500 grams, or about five cups) of flour with about seven ounces (200 milliliters) of water (perhaps a little less) and a teaspoon of salt. Drop spoonfuls of the dough into the boiling water until there’s no space left at the bottom of the pot. “When the balls start swimming,” Wilma says, “the dumplings area ready.”

You can serve your goulash and dumplings with a dollop of sour cream or crème fraiche. And of course, you can make less of this recipe by lessening the ingredients proportionally.

♦ Mashed Potatoes. You might think of this beefed-up, spiced-up version of a traditional side dish as a sort of Ethiopian shepherd’s pie.

Begin by putting one kilogram (about two pounds) of peeled potatoes in a pot of cold water – enough to cover them – salt the water to taste, bring it to a boil, and simmer until the potatoes are very tender, about 30 minutes, depending on the size of the potatoes (if you cut them into pieces, they’ll cook faster). Wilma recommends floury potatoes rather than waxy ones. When the potatoes are tender, mash them into a purée.

Next, bring 250 ml (about 8.5 ounces) of milk to a boil, add it to the potatoes, and stir the ingredients together until they form a soft paste, then add a touch of nutmeg (Wilma prefers a “big touch”). You don’t want them to be liquidy because they need to absorb the sauce (which is the next step).

Finally, melt one and a half teaspoons of butter in a pan and add one-half kilogram (about one pound) of ground beef. Add berbere to taste – Wilma likes it hot, so she uses three or four teaspoons. Stir the ingredients together, then let them simmer at a low heat until the meat is cooked. You may need to add some water along the way, little by little, to make it saucy. When the spicy meat it ready, you can serve it atop the potatoes or alongside them (see photos above).

THAT SHOULD GIVE YOU PLENTY OF OPTIONS for your Ethio fusion entrées and appetizers, so let’s move on to desserts. Ethiopia isn’t a sweets culture, and there’s no word for “dessert” in Amharic. But leave it to Wilma to come up with some desserts that use unique elements of traditional Ethiopian cuisine.

Bula – one of the acquired tastes of Ethiopian cuisine (if you ask me) – is a powdered form of enset, a tree used in many Ethiopian cultures as a vital sources of food. Ethiopians turn the trunk of the enset into qocho, a fermented bread-like food, and use the powdered form to make the porridge bula, which (if you ask me) requires lots of rich niter kibe and other spices to overcome its gummy consistency.

The next three recipes call for bula, but Wilma recommends that you mix the bula in each case with just a touch of cold water before combining it with the hot ingredients. When bula hits hot water, it tends to clump. So the cold water prepares it a little better for its final resting place.

♦ Bula Pudding (Bertu Bula). This dessert, which looks like a pudding (see photo), adds spices and flavors to bula that greatly enhance its taste. Wilma’s nickname for it is bertu bula, taken from bertukan, the Amharic word for an orange.

To make it, boil three cloves, a one-inch piece of ginger and one star anise in 50 ml (two ounces) of water for five minutes. Let it stand for a few minutes, then remove the spices from the water and add 200 ml (about seven ounces) of fresh orange juice with the pulp.

Now, add one and a half tablespoons of bula and two teaspoons of sugar (more or less to taste). Bring everything to a boil for five minutes. Chill the dessert in the refrigerator before serving. Wilma recommends decorating it with mint and papaya glacé (sugar-glazed papaya).

♦ Fortified Bula Pudding. Here’s another take on a bula pudding, this time with a bit of liquid courage.

Begin by stirring one and a half heaping soup spoons full of bula powder into 300 ml (10 ounces) of milk and let it cook gently for about five minutes. You can add a little more milk if it begins to thicken too much. When it’s cooked, pour in 40 ml (about one and a half ounces) of elderberry liqueur (Wilma’s preferred variety) or any liqueur of your choosing, and continue to stir until it reaches a pudding-like consistency. Pour the finished pudding into a bowl, and after it cools a little, put it in the refrigerator to chill. Sprinkle it with dabs of elderberry jam before serving (see photo below).

If it’s not sweet enough for you, add a little more of the liqueur. You can substitute syrup if you want the dessert to be non-alcoholic – not that anyone would, of course.

♦ Bula Jello (Tafach Bandira). This dessert, once again using bula powder, doesn’t jiggle like real Jell-O does. So just as Wilma has appropriated the name, I’ve adapted it (what a difference a hyphen makes!). This complex dessert has three steps, each one corresponding to a color of the bars on the flag of Ethiopia. In fact, Wilma’s Amharic name for this dessert, tafach bandira, means “sweet flag” in Amharic.

One thing to note: For this, you’ll need a fruit-flavored wine and a piece of fresh fruit matching the flavor. Wilma recommends peach, but if you use a wine with a different flavor, then use the appropriate matching fruit.

In step one (green), blend 200 ml (seven ounces) of wine with a peach note, one tablespoon of bula, one or two tablespoons of sugar (to taste), and two or three drops of green food coloring. Next, peel a vineyard peach (sort of shaped like a flying saucer) and cut it into little pieces. Bring the wine and bula to a boil and let it cook for a few minutes until it begins to thicken, then transfer it to a bowl and add the peaches.

For step two (yellow), mix 200 ml (seven ounces) of the syrup from a half-pound can of pineapples with a tablespoon of bula, add two or three drops of yellow food coloring, and let it cook for a few minutes. When it thickens, put it into the bowl with the peaches and add some diced pineapples.

Finally, in step three (red), cut five strawberries into little pieces, taking care to sort out white parts (if there are any). Put them in a pot, add 50 ml (two ounces) of water, two teaspoons of sugar and the juice of half a lime. Let it cook until the strawberries are very soft and easy to mash. Now, in a bowl, mix one tablespoon of bula with some water and add this to the strawberries. Let it cook for a few minutes, then add two or three drops of red food coloring.

When the strawberries are ready, pour them into the bowl with the other ingredients and let it cool in the refrigerator. When it’s ready to serve, invert the bowl so you have a round gelled dessert with layers of green, yellow and red from top to bottom, just like the colors of the Ethiopian flag.

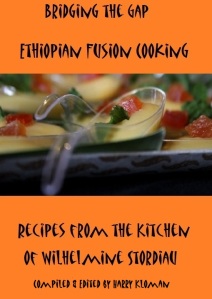

♦ Strawberries Jubilee Fitfit. This is a relatively quick and easy dessert – once you get the hang of making fitfit with the right consistency. The photos above and below show you two different ways to serve it.

Begin my tearing three pieces of injera into little chunks. Boil about a cup of water (250 ml) for about 10 minutes with two or three cloves, a cinnamon stick of a few inches long, one star anise and an inch-long piece of fresh ginger. Let it cool, remove the spices, then blend it into the injera pieces to make your fitfit. Feel free to use your hands to mash it all together (that’s what I do).

When the fiffit is ready, mold it into a roll and wrap it very tightly with film (plastic wrap or wax paper). Close the two ends of the wrapping, and put it into the refrigerator for 24 hours. Now, cut some strawberries into bite-sized pieces, put some sugar and lime on them (to taste), and put them into the fridge as well.

The next day, carefully cut the fitfit role into slices, and serve with the strawberries. You can also add dollops of your favorite yogurt. In fact, feel free to puree some strawberries into your plain yogurt to enhance this dish. The photos above and below offer serving suggestions. Wilma also suggests crème Chantilly (whipped cream flavored with vanilla) as a nice garnish.

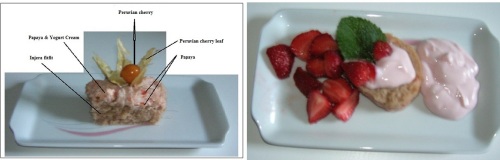

♦ Papaya Fitfit. Here’s a unique dessert with some unusual elements, although the ingredients are certainly fungible: You can substitute mango for the papaya, and such things as cherries, blueberries or raspberries for the Peruvian cherries – a tomatillo-like fruit which, I suspect, you can only get in a big city at a well-stocked produce market (at least in the United States).

Making this is a two-day process if you want to do it the way Wilma does. So on day one, take about a cup (250 ml) of plain yogurt, wrap it in cheesecloth, and put it in the refrigerator. This lets the water drain from the yogurt.

The next day, blend 100 ml (three to four ounces) of cane sugar syrup, or more if you want it sweeter, with 200 ml (about one cup) of chilled Ethiopian coffee or espresso. You can also add a rue leaf if you have one in the garden, Wilma says. Now, chop up three pieces of injera, and use this sweetened coffee concoction to make your fitfit. Add the liquid slowly, in batches, to get the right consistency: not too dry, and certainly not soggy.

When the fitfit is ready, line a square bowl or tray with some film (again, plastic or wax paper), and put the fitfit into it, pressing it well to make it look smooth and even.

Next, cut up and mash the flesh of one half of a large papaya, then blend it into 250 ml (about one cup) of yogurt, using a spoon to stir and crush the ingredients into a nice cream. Spread the papaya yogurt cream on the fitfit, cover it, and refrigerate for two hours.

When it’s ready, you can “pull up the whole ‘cake’ with the wrapping and put it on a plate,” Wilma says, or you can cut it into squares. Decorate it with the Peruvian cherries, and if they came with their leaves, you can use them to enhance the presentation (see the labeled photo above). You can also decorate with little nibbles of papaya: Remember that you still have the other half of it left. The color of your finished dish will vary depending upon the color of the papaya that you used. And of course, if you choose to use mango, it’ll probably turn out to be orange.

About those Peruvian cherries: This is a species of fruit called Physalis peruviana that also goes by the name Cape gooseberry (among others, including aout in Amharic). It’s sort of like a tiny yellow tomato, so if you prefer more conventional fruit sprinkled on your dessert, just choose something equally small and decorate accordingly. You could even use tomatillo (Physalis philadelphica) as a substitute. It is, I suspect, easier to find.

♦ Nefro. This unusual dessert recipe has no unique Ethiopian ingredients, although it does use some spices that are important in Ethiopian cuisine. It’s another example of Wilma’s gastronomic imagination, and the name of the dish is an Amharic word that refers to boiled grains. The recipe does call for a little bit of Begena katikala, but you can substitute vodka. Katikala is a traditional Ethiopian grain alcohol that Wilma’s company makes. She only sells it in Europe, and you won’t find katikala anywhere else in the world outside of Ethiopia.

To make Wilma’s nefro, begin by washing and then soaking 60 grams (about two ounces) or wheat kernels – sometimes called wheat berries – in water overnight. You can substitute spelt or any other small-kernel grain.

The next morning, boil one liter (about 34 ounces) of water with the following ingredients: seven cloves, three cardamom pods, a one-inch stick of cinnamon, and a one-inch stick of ginger. Strain out the spices, put the washed wheat into the spiced water and let the wheat cook until it falls apart. You may need to add a little water as it cooks until it’s done.

When it’s ready, you have two options: You can blend it all into a purée, or you can keep it a little “lumpy.” As Wilma explains it: “I personally like some whole wheat in the pudding, so if you are of the same opinion, take a few spoonful away and blend the rest with your mixer. Return what you have taken prior to blending and stir.”

Next, add five tablespoons of cane sugar, then stir in 50 grams (about one and a half ounces) or candied lemon peel or another candied fruit chopped up into little pieces. Finally, add two or three tablespoons of katikala or vodka.

Put the finished dessert into a bowl and let it cool in the refrigerator. When it’s ready to serve, you can sprinkle it with powdered sugar and serve it with a dollop of whipped cream on the side (see photo).

LIKE MOST CREATIVE PEOPLE, Wilma can’t really explain how she comes up with a new dish or a variation of something that already exists. But she can say that the process begins by placing no limitations on your imagination.

“My philosophy, if you can call it such, is that there are no don’ts,” she says, “not in cooking nor in drinking. It has to be tasty, that is all. But how can you define tasty? What can be tasty for me is maybe horrible for you. Taste is something we grow up with and learn from our environment. When I think of the decomposed fish in Finland, my god! On the other hand, I like bula.”

For example, take the mushroom: It’s called indugay in Amharic, and you can now get indugay wot, a spicy mushroom stew, in Ethiopian restaurants around the world.

“The more common name for mushrooms in Ethiopia is ‘umbrella of the devil’ – je setan jantela,” Wilma says, “and back in Ethiopia, I never recall having it as a wot.” The cooks in her home didn’t prepare it when she was growing up, although it’s a beloved dish in other parts of Ethiopia.

And why, she asks, do people take to some new food items but not others: “When we eat shrimp, we go yum yum, and it’s regarded as a high-range food. But if you eat grasshoppers, one makes a funny face, even Ethiopians.”

Wilma says she’ll only eat chicken (doro) when it’s prepared by Ethiopians, and “I would never eat any doro if not cleaned by an Ethiopian or by myself. One should break the traditions and keep them as well. I hate it when someone says, ‘I have never seen it done this way.’ So what! Is it good or isn’t it good? That’s what matters.”

Aesthetics are also important when Wilma creates a dish, and that presents her with another challenge. “Certain things are very good but do not look right,” she says, “and this is what needs to be polished and becomes time consuming.”

For Wilma, it’s all about the new. “I just like creating things,” she tells me, “and once they are created, they do not interest me very much.” During our conversations, I introduced her to tihlo, a dish from northern Ethiopia: It’s small balls of roasted barley flour moistened with water, and you dip the balls into kulet. So now, she tells me: “I am thinking of two variation of it, but before doing so I need to make it and taste it. For the one version, it will definitely work out to have it served not only with kulet but with wot and call it Ethiopian fondue. The second could be a dessert, but I need to think more about it.”

At home, Wilma makes Ethiopian food about once a week, “but we have Ethiopian taste nearly every day,” she says, because she uses berbere and awaze to spice other dishes.

“Berbere becomes a drug for certain persons,” she adds. “Thank god you can get it everywhere nowadays. But when we came to Europe from Ethiopia [in the 1970s], it had to come from back home, and that was very difficult.” She counted on travelers – friends, pilots, stewardesses, even strangers – flying from Ethiopia to Germany to stock her kitchen.

So when will Ethiopian become the new Chinese? When will it become so well known and ubiquitous that you can get it in non-Ethiopian restaurants? And what has the diaspora done to cooking traditions outside of Ethiopia?

“I do not know how is was in the U.S.,” Wilma says, “but in Ethiopia and Europe, when Chinese restaurants first opened, you had no choice: You had to eat with chop sticks, drink your tea without sugar, and no bread was allowed. Later on you could ask for cutlery, and now you have to ask for chop stick.”

In other words, things change, and not always for the better if authenticity is your desire.

In India, people traditionally eat with their fingers, but Wilma notes that Indian diaspora restaurants never tried to get people to do that. Ethiopians, however, have never abandoned injera, although Wilma does see more Ethiopian restaurants in Europe offering cutlery to people who request it.

Still, there’s something special about eating an Ethiopian meal the traditional way. “Some Europeans do not like eating with their fingers,” Wilma observes. “My husband and eldest daughter never use their hands, even at home. My brother is the same. Yet all of these people love Ethiopian food.”

“For Europeans,” Wilma adds, “Ethiopian food does not look good. It takes an effort to have them taste it. But after they do, nobody can hold them – it’s just like a horse going back to his home. Restaurants do try more and more to have a nice-looking plate, but this is maybe where something more has to be done.”

Wilma notes that most Ethiopian restaurant owners in Europe are not professionally trained chefs: They’re just everyday women and men who like to cook and do it well enough to serve it to others. That can be a good thing because it means they may be more tied to tradition.

For example, the dish called zilzil is made with long strips of beef rather than the smaller chunks of beef used to make a wot. She recalls a German journalist who interviewed a cook while she was preparing zilzil, and the journalist asked how long she would make her strips of beef. “Sometimes I can get it a meter long,” the woman told him. “Afterward in the report,” Wilma says, “you heard the journalist complaining about this long piece of meat. But the longer the zilzil, the more professional you are.”

Finally, though, Wilma does see a problem with Ethiopian cooks of the diaspora.

“The feeling I have is that not only Ethiopians but Africans in general do not value their traditional foods as they should,” she says. “Wine is better than t’ej. Vodka is better than katikala. This makes the prices of t’ej and katikala lower. Although many dishes and restaurants are of a very high standard, Ethiopian food is ‘cheap’ if you compare it to what you get for the same price somewhere else.”

So she’d like to see Ethiopian cooks innovate, and she’d welcome such innovation with Ethiopian cuisine in non-Ethiopian restaurants:

“Ten years back, people didn’t even know what chicken tandoori was, but now it is part of the international cuisine. Many French think that couscous is a traditional French dish. And imagine that a wurst [hot dog] seller made a lot of money selling curry wurst, and she had the patent for her idea registered.”

Let’s hope Wilma has a few patents pending for her unique creations as well.

Harry Kloman

University of Pittsburgh

COPYRIGHT NOTE: All of the images in this post are owned by Begena Tedj.

Leave a comment